In the pandemic era, awards shows have continued a steady decline in terms of viewership that began at least a decade ago. There are numerous explanations for why there is dwindling interest in events like the Golden Globes or Academy Awards, but it is not my intention to delve into said explanations here. One thing is for sure: viewership for award shows peaked in the late-1990s. For example, 57 million Americans watched the 70th Academy Awards on March 23, 1998, where Titanic won best picture. By comparison, this year’s Oscars telecast was only watched by 10.4 million Americans. Similar trends are identifiable for the Grammys and Emmys. Award shows are no longer in vogue.

There was a time, however, when audiences, sponsors and peers considered a filmmaker winning an Academy Award as the pinnacle of success for a person involved in filmmaking. Perhaps this is still true, even if sponsors have lost interest and such award shows have become less and less palatable for viewers at home.

What does this have to do with comic books? Specifically, what does this have to do with Canadian comic books? In and of itself, very little. Indeed, numerous animators from Canada have worked on films that have won major awards as part of teams (especially Disney animated features) and some of these people have been involved in the Canadian comic book scene. Yet, animators tend to be the types of hidden labourers who do not generally receive individual accolades from institutions like the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. In terms of animation, when it comes to such awards, directors and producers get most of the attention.

With all of this in mind, what if I told you that a Canadian underground comix creator would go on to become one of the country’s most celebrated animators and future Oscar winner in the late-1970s? Then what if I told you that a prolific mini-comic creator from the mid-1980s would go on to be nominated for (but not win) an Academy Award decades later and that this person published over forty comics while still in high school?

Both stories are true, but this month I will focus on the creator who won the Academy Award: John Felix Weldon. An overview of the works of the creator who was nominated for an Oscar (and ultimately lost), Graham Annable, is a story for another day. Let’s get started.

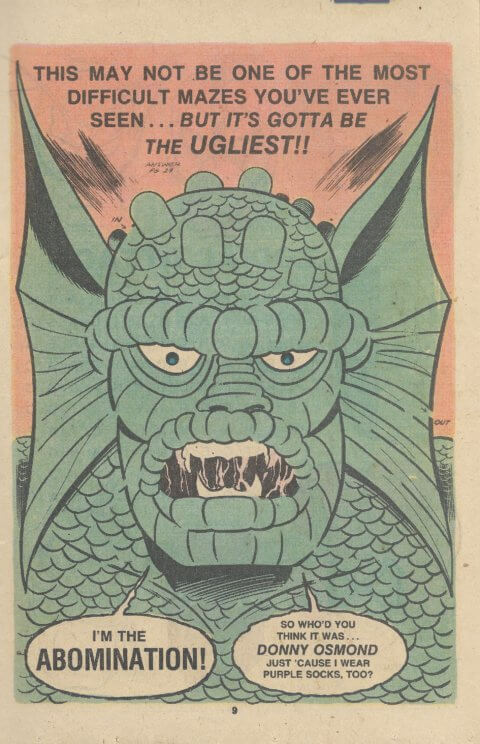

There is a plethora of “one and done” comics from the Canadian Silver Age (what I like to call “orphan” comics). Some of these comics are one-shots that were never intended to become series. Others failed to catch on or led to creators deciding that self-publishing comics was more trouble than what it was worth. In other cases, a person created a comic with the intention of breaking into the industry but then decided to pursue other creative outputs. There are many examples of orphan comics from the Canadian Silver Age where a creator (or group of creators) published a single comic and then disappeared from the scene altogether. There are quite a few comics from the 1970s like this that I hope to cover here someday, including undergrounds like Hierographics, Flash Theatre and London Life: Graphic Entertainments and non-underground titles like 1975’s John Ward Secret Agent. These comics have faded into the background and have been lost to time because they did not launch the career(s) of creator(s) who became noteworthy later. There is one exception to this from the early days of the Canadian Silver Age: The Pipkin Papers.

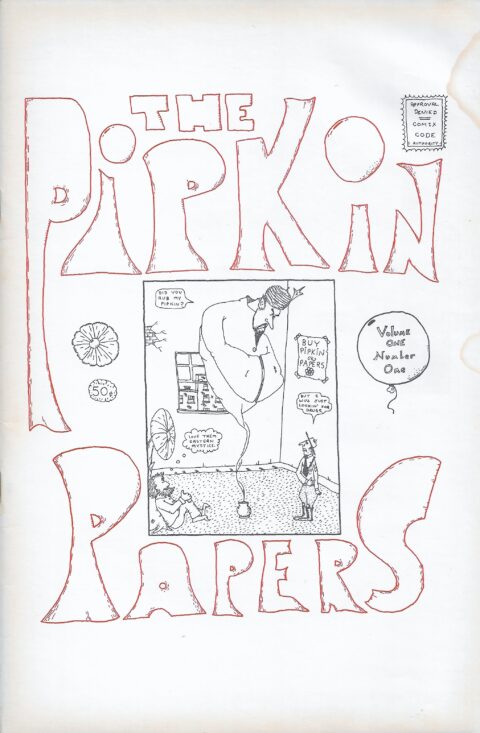

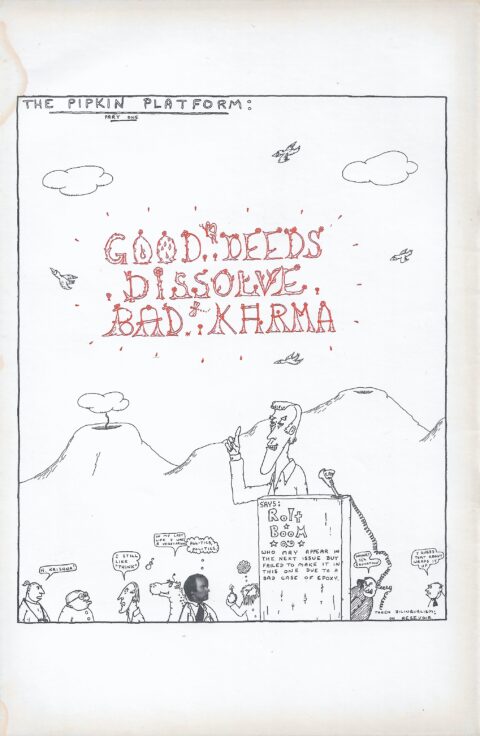

John Weldon was born in Belleville, Ontario, in 1945, but was raised in Montreal. As a young man, he studied psychology and mathematics at McGill. By the late-1960s, he became involved in fine arts. In 1967 he wrote the musical comedy Genius is a Four Letter Word, which was performed at McGill. Then, in 1969 he released The Pipkin Papers, a one-shot underground comic that was among the first underground comix released in Quebec and may be the first English language underground published in the province.

The Pipkin Papers was edited by Wolf Krakowski, a Polish-Canadian singer and guitarist who was involved in street theatre at the time. Krakowski would release two Yiddish language blues/reggae albums from 1996-2002. It was drawn by Weldon with storylines by “Rhad Gmal,” which I believe to be a fake name and I have long assumed that Weldon wrote the stories in the comic too. The entire comic is available on Weldon’s website.

The comic itself consists of two unrelated stories. The first, “Saturn” focuses on the adventures of two Canadian astronauts who crash land on the planet of the same name and find it teeming with life. The second story, “The Thinker,” is based on Genius is a Four Letter Word and focuses on two biochemists in Montreal who are conducting experiments on themselves with drugs. The experiments lead to one of the scientists gaining superpowers. Both stories are filled with absurd humour but are tame compared to many of the stories that came out of the underground comix movement at the time. The artwork is crude, but stylistically interesting and is an early glimpse at what would become the part of the distinctive animation style of the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) from the late-1970s through the 1990s.

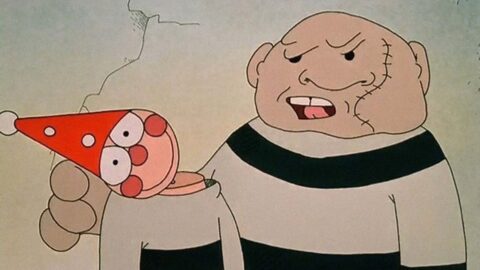

Weldon joined the NFB in 1970, where he would work for more than thirty-three years as an artist, writer, songwriter, and director. By the time he retired in 2004, Weldon had worked on more than fifty films for the NFB, directing twenty of his own animated shorts. Weldon directed his first two films in 1977. The first was No Apple for Johnny, which tells the story of the obstacles facing a teacher trainee. However, it was 1977’s Spinnolio that ended up being his breakthrough short. The film is a parody of Pinocchio and tells the story of a lifeless puppet that is forgotten by the fairy godmother but nevertheless climbs the ranks of a company’s human resources department only to be replaced by a computer. The film won Weldon the Canadian Film Award for Best Animated Short in 1977. The awards would be renamed “The Genies” in 1980 and would merge with the Gemini Awards in 2012 to become the Canadian Screen Awards.

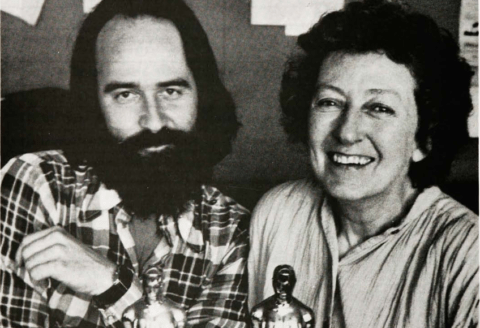

Weldon’s rise to fame in the world of animation was swift. His next film, 1978’s Special Delivery, is a Canadian classic. Co-written and co-directed with Eunice Macaulay (who had worked as an animator on both No Apple for Johnny and Spinnolio), the film tells the story of Ralph, whose wife orders him to remove snow from the steps on their front porch. Ignoring his wife, Ralph later finds the mail carrier has slipped on the ice on the steps, broken his neck and died as a result of his tardiness. Hijinks ensue after Ralph attempts to cover up the mailman’s death. The film remains one of the best-known animated shorts ever produced by the NFB and won Weldon and Macaulay the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film at the 51st Academy Awards in 1978. In less than a decade, an obscure underground comix creator from Montreal had won an Oscar.

Special Delivery was the second of three consecutive Academy Awards in the category won by NFB filmmakers and was part of an era when the NFB was one of the world’s premier creators of short films (both live-action and animated). Of importance for Canadian comic book collectors and enthusiasts of the Canadian Silver Age is that Weldon was the only one of these creators who was directly involved with the creation of a comic book during this era.

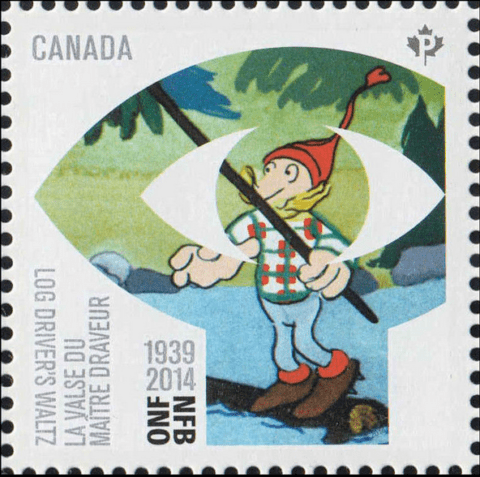

Weldon and Macaulay’s Oscar win may have been the pinnacle of award show success for the duo, but Weldon was really just getting started. His next film is arguably the most beloved animated short ever produced by the NFB: 1979’s The Log Driver’s Waltz. The film tells the story of a young woman who decides to marry a log driver instead of more affluent or better-educated suitors. The animation is set to (and based on) Wade Hemsworth’s song of the same name, as performed by Montreal folk singers Kate and Anna McGarrigle. The film was played on Canadian television regularly during the 1980s and 1990s as part of the Canada Vignettes series and remains the most downloaded of the NFB’s short films in the internet era.

Weldon continued to direct experimental animated shorts for the NFB over the next three decades. Some highlights include 1984’s Real Inside, which mixes live-action and animation in a way that anticipates Who Framed Roger Rabbit? Weldon’s film tells the story of a toon named Buck Boom who attends an interview for an office job. The film tackles issues of difference, prejudice, and racism through the relationship between toons and non-toons.

Weldon’s work became more philosophical as his career went on. His 1990 film, To Be, deals with issues of morality and ontology and was nominated for the Palme D’Or at Cannes that year (ultimately losing to Adam Davidson’s The Lunch Date). Weldon’s follow-up was 1991’s The Lump, which would be nominated for a Genie Award in 1992.

By the late-1990s, Weldon was collaborating with American producer Marcy Page (who dominated the Genies at the time). The pair would be nominated a Genie Award in 1998 for the short film Frank the Wrabbit, ultimately losing. Weldon would finally win the award in 2002 (with Page) for The Hungry Squid. Weldon’s final film for the NFB would be 2004’s Home Security.

After Weldon retired, he continued to be involved in creative projects and was particularly focused on songwriting and animated shorts during the flash era, as well as a return to creating webcomics with his series Ashcan Alley (apparently some of his Ashcan Alley comics have had physical releases, but I have not been able to find examples of any of them). Until 2014 he regularly posted on his website, “Weldon Alley.” Since 2012, his webcomics have been available on his Flickr account, where he recently wrapped up the tenth season of his series. He also still regularly uploads videos promoting Ashcan Alley to YouTube.

In his retirement, Weldon came full circle by returning to comics with Ashcan Alley and maintained a presence by adapting his creative impulses to various multimedia outlets and opportunities on the internet. Yet, when one looks at his career, it is obvious that The Pipkin Papers is what started it all. In fact, in 2008, Weldon told the Montreal Gazette’s Bill Brownstein that he credited his comic with getting him the job at the NFB.

Although Dan, Victor and I have encountered conflicting reports about the print run of The Pipkin Papers, it remains a scarce and desirable book for Canadian Silver Age collectors. Some sources suggest that the comic had a print run of only 600 copies, but Weldon himself has stated that the print run was 2500 copies. I am inclined to believe that the comic had the larger print run, as Weldon suggests, as the comic comes up for sale more often than similarly scarce Canadian underground comix from the era. In fact, I am aware of two copies that are currently at market and during the past few years there is usually at least one copy available at any given time. Also of note is that The Pipkin Papers is represented in the CGC Census, with four copies currently graded (the highest-graded copy being a 9.2).

Despite the fact that this is on the radar of underground comix enthusiasts and Canadian comic collectors alike, I consider it undervalued in today’s market. Expect to pay between $100 and $200 CAD for a specimen, depending on condition. I procured my own, stained copy of the comic in 2017 for around $50 CAD, which I still consider a steal, despite its lesser condition.

Ultimately, The Pipkin Papers is one of the most important one-shots of the Canadian Silver Age. The fact that it still comes to market regularly and remains affordable shows how important comics from the Canadian Silver Age continue to be neglected by the wider collectors market (other than early issues of Cerebus). Weldon is one of the great masters of Canadian animation and the comic that started it all should be on the wish list of all Canadian collectors.

Great article, brian. I’ve never heard of any of these comics. The research that you put into each article you write is simply amazing.

By the way, the new CBD format capitalizes your first name.

Thanks, Klaus. I really appreciate your compliment. I did notice that the new format capitalizes my first name. I will have to see if this can be fixed before next month’s article. Cheers, brian

Hey brian, I saw on the CTV local news where there was a comic makers’ show in Dartmouth. I think that’s down by your location. It featured a bunch of Canadian-created original comics. Did you attend?