One of the most disheartening things about collecting and researching independent comic books from the late 1980s is knowing that the market collapsed before the decade ended. The simplest explanation of the crash is that the sheer volume of mediocrity that was hitting the shelves in order to meet the demands of (and take advantage of) the speculators market at the time led to an epic crash. People were buying black and white comics hoping that they would end up with the next Cerebus the Aardvark # 1 or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles # 1, gambling that said comics would become the next valuable collectible. This led to a plethora of would-be and wannabee creators taking the leap of faith into making their own comic book (or series) dreaming that they would become the next Dave Sim or Eastman & Laird. Yet, speculator bubbles never last forever. Decades later, every comic book shop in North America still has a long box (or boxes) filled with amateurish black and white comics that few people remember and even fewer people want. Dollar bins are polluted with these things. They are ubiquitous.

In the past, these sorts of comics have been profiled on internet blogs for the sake of comedic effect. Making fun of amateur and unsuccessful comics from a bygone era is low-hanging fruit. Making a comic book is hard work and even if the end result of the creators’ efforts is suspect, it is important to remember that creating such works was part of someone’s dreams and ambitions. Lately, I have become more aware of a burgeoning shift in interest towards some of these kinds of books due to the YouTube channel Power Comics and Robin Bougie’s new magazine Gutter Hunter (which I discussed last month). I have always grabbed questionable black and white comics from the Canadian Silver Age when I have found them during my travels over the years, but lately, I have started to rethink these “gutter books” as more interesting historical art objects that are worthy of a closer look.

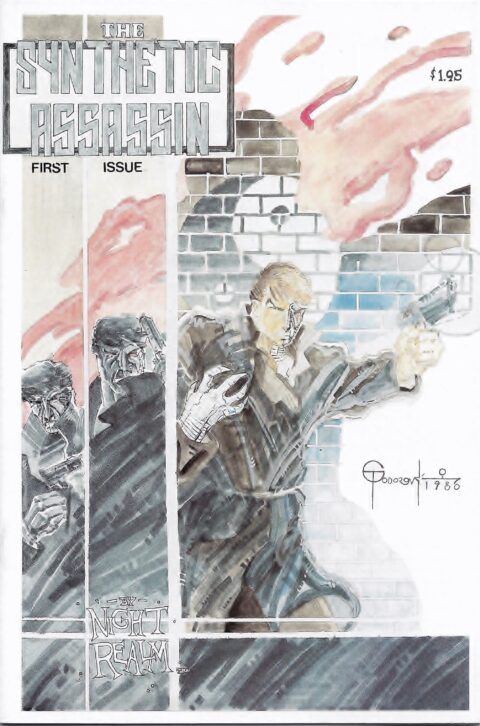

I have several amateur black and white Canadian comics from the 1980s that fit the bill, but one series that really stands out to me is The Synthetic Assassin. This three-issue series debuted in 1986 and was the brainchild of comic collector Fred Diana. The series was published by Diana’s imprint Night-Realm Publishing, which was based in Islington, Ontario. From 1986-1996, Night-Realm would release ten individual comics.

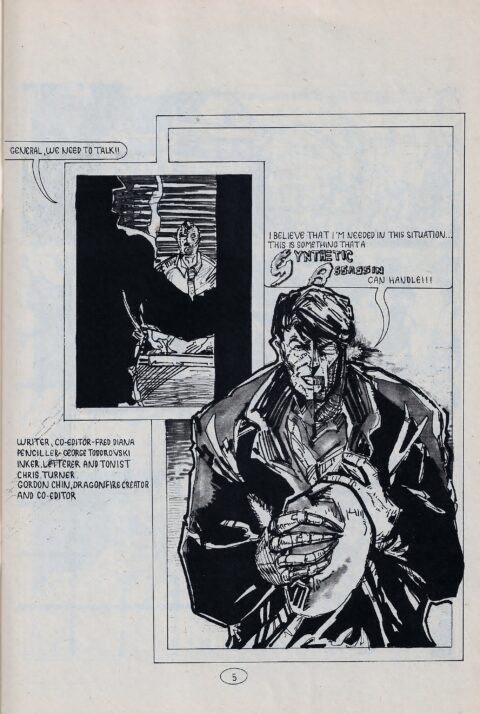

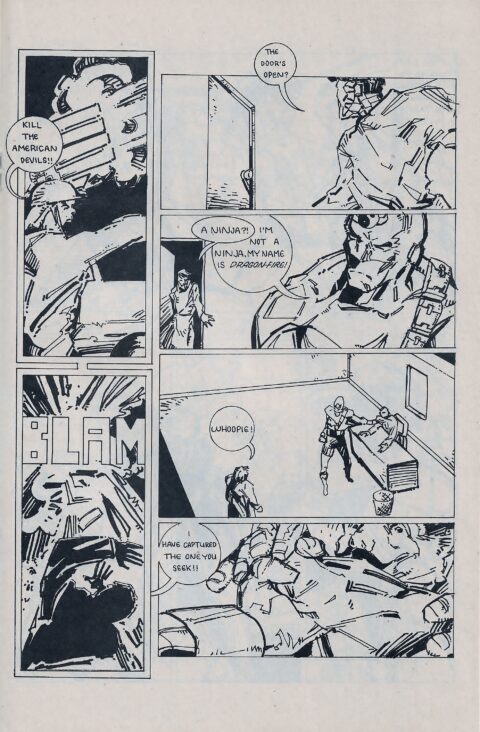

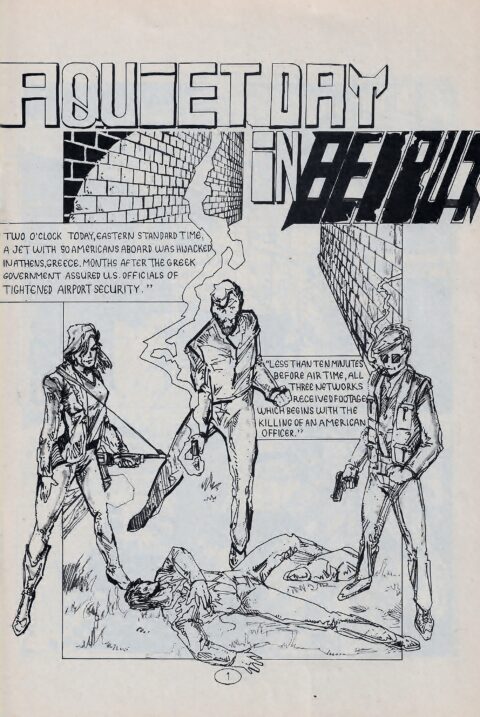

The Synthetic Assassin # 1 is an explicitly amateur affair. Rather than hiring an experienced artist to bring his vision to life, Diana and his co-editor Gordon Chin employed two fifteen-year-old boys to create the comic. George Todorovski provided pencils for the issue, while Chris Turner acted as the inker and letterer. Readers will immediately find themselves looking at a comic where the creators bit off more than they could chew. The artwork is inconsistent and mostly devoid of backgrounds, while the lettering is also inconsistent and is riddled with spelling and grammatical errors.

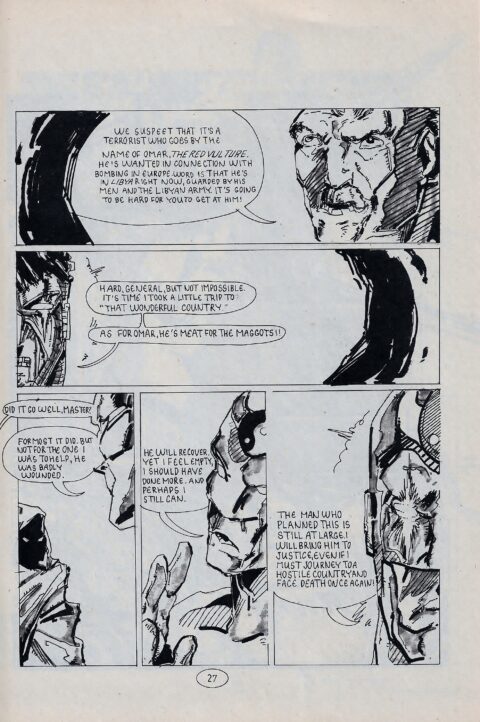

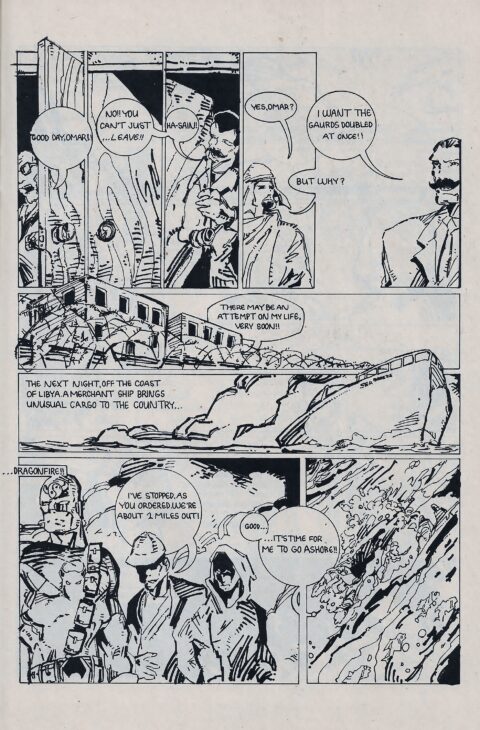

The comic follows the titular Synthetic Assassin who is sent to Beirut to attempt to rescue hostages who have been captured by a terrorist during a jet hijacking in Greece. The father of one of the hostages reaches out to a different hero, Dragon-Fire (who is credited to Gordon Chin in the indicia) to try to rescue their loved one. This leads to the two heroes on something of a collision course. The issue ends with the Synthetic Assassin rescuing all but one of the hostages and killing the terrorists, while Dragon-Fire provides support. However, the characters do not have a face-to-face encounter and the Synthetic Assassin does not seem to be aware of Dragon-Fire’s presence. As the issue ends, we learn that the person who organized the hijacking (a character named Omar, The Red Vulture) is still at large.

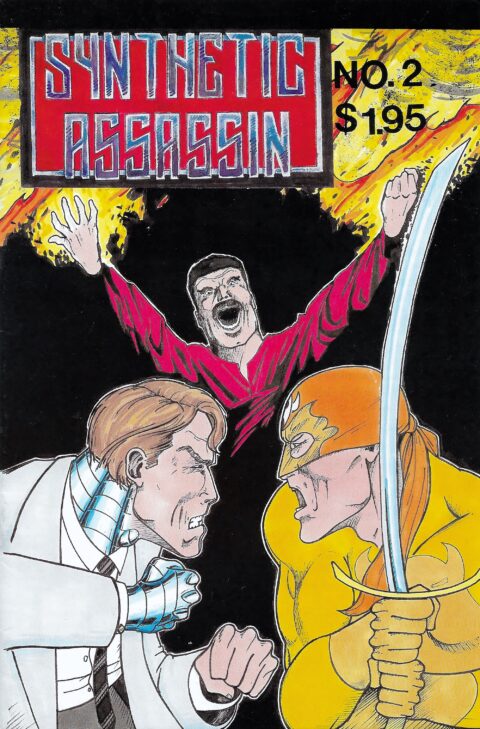

Most comics like this did not find a large enough audience to justify a second issue. Somehow, The Synthetic Assassin did. Although Diana originally planned for issues to be released quarterly, the second issue did not appear until 1987.

Issue # 2 begins with something that I have never seen in a comic before: an introduction that serves as an apology for the poor quality of the first issue. Diana and Chin effectively throw Todorovski and Turner under the bus and use the apology to announce that they are leaving the series and are being replaced by artist Kyu Shim and inker Scott Wylie beginning in issue # 3.

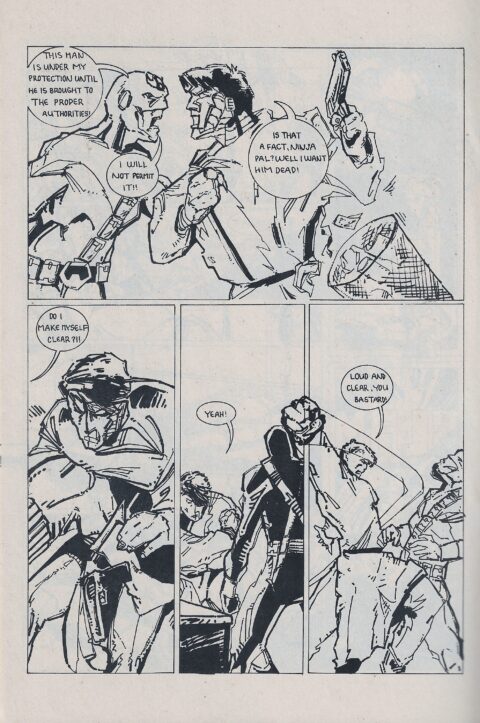

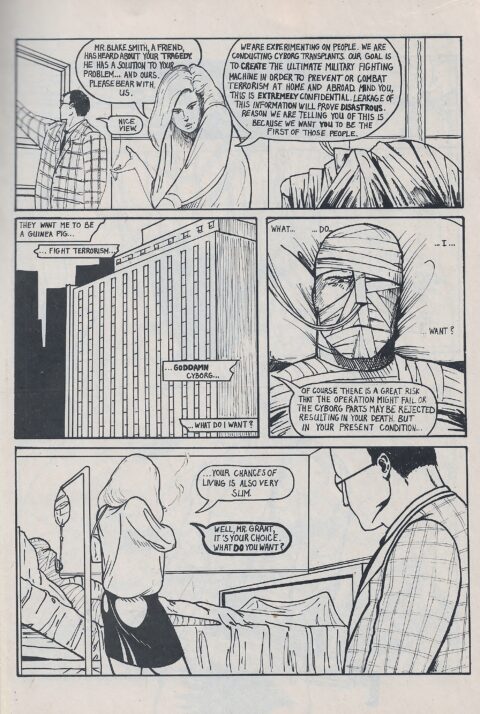

The artwork and dialogue are noticeably improved here, but the second issue is still an amateur affair. The issue offers a glimpse of an origin story for the title character, which seems like something of a riff on Robocop. The comic predictably follows the two heroes attempting to track down the Red Vulture in Libya.

The source of conflict here, however, is between the two heroes. Dragon-Fire hopes to capture the Red Vulture and bring him to Europe to go on trial for his crimes. On the other hand, the Synthetic Assassin’s mission is to murder the villain for the American government.

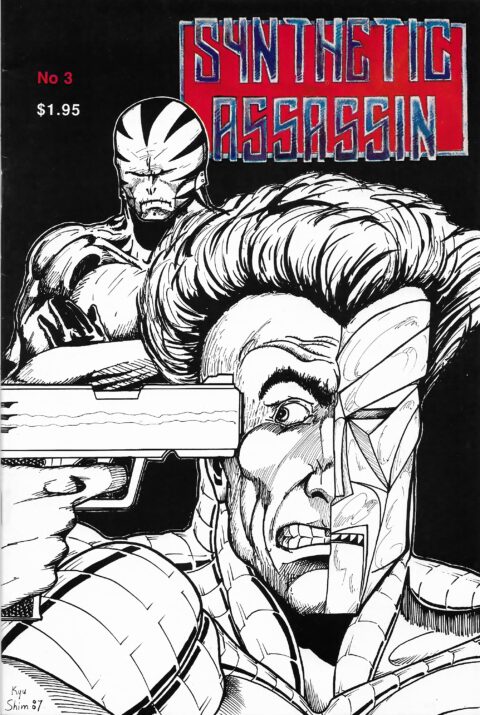

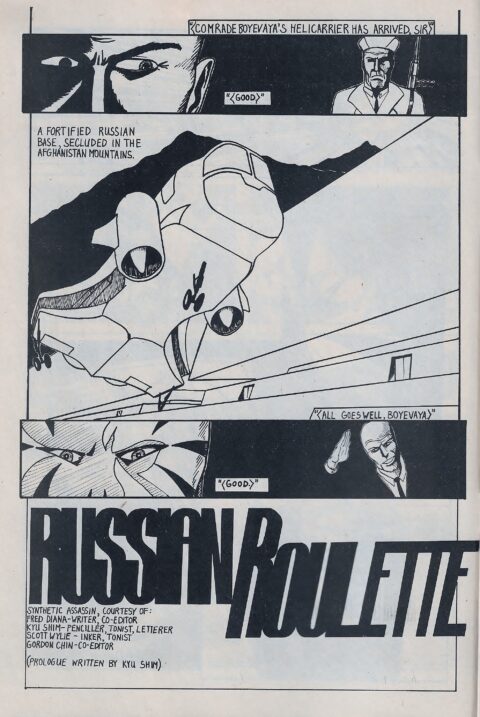

The third and final issue of The Synthetic Assassin did not appear until 1988. Like the second issue, the comic begins with a bizarre introduction from Fred Diana. This time, he laments the collapse of the black and white comic market that began in 1987, blaming “too many books with ninja animals in them” and the lack of quality books on the shelves for the industry-wide downturn. Although I agree with this sentiment from an historical perspective, there is a certain irony to Diana’s remarks. The remainder of the introduction introduces readers to the new creative team of Kyu Shim and Scott Wylie, while also describing plans for a fourth issue of the series (which was never released).

The artwork and lettering do show improvement in the third issue of the series, but both Shim and Wylie were inexperienced and similar problems emerge concerning the quality of The Synthetic Assassin # 3.

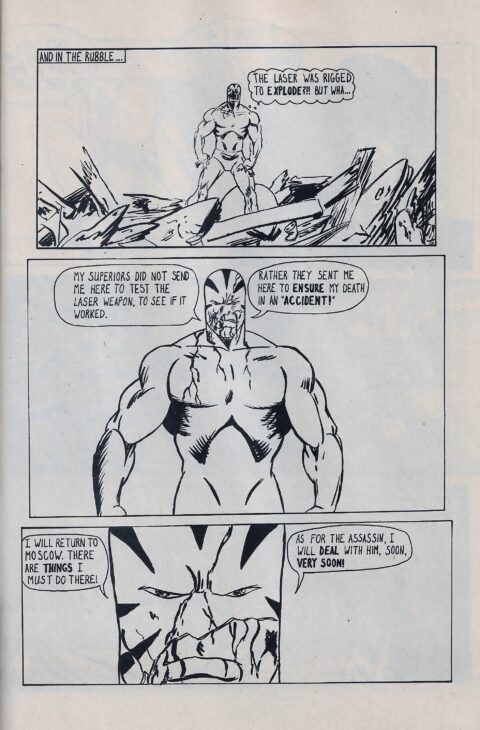

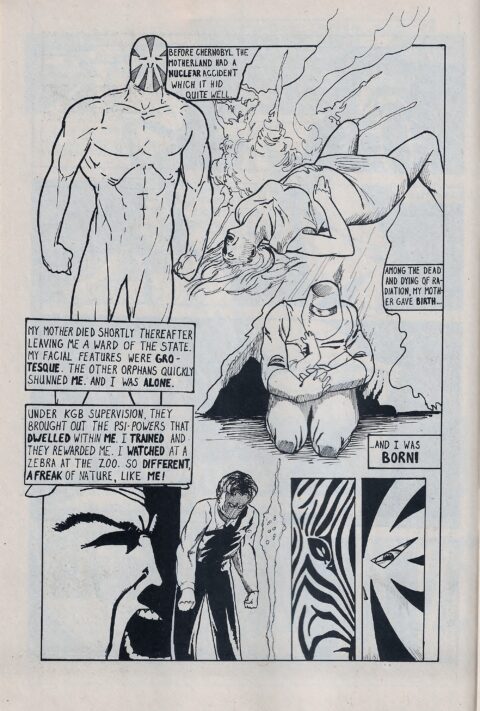

Narratively, the comic is a departure from the first two issues. Dragon-Fire is nowhere to be seen and the setting shifts to Afghanistan, where the Synthetic Assassin has been captured by a Russian psionic super-soldier named Boyevaya.

We quickly learn that Boyevaya’s mother was irradiated and that he was born disfigured, but with psionic powers. During his childhood, he took a liking to Zebra’s justifying his striped mask disguise.

It is revealed during the issue that Boyevaya has captured the Synthetic Assassin and is using his powers to probe our hero’s memories. As a result, we learn more about what led to Blake Smith becoming a cyborg.

Inevitably, the Synthetic Assassin breaks free and fights with Boyevaya. The comic ends with Boyevaya’s laser cannon exploding due to sabotage and the Synthetic Assassin escaping. The ending is intended to set up additional issues and storylines, but the series would end here. The collapse of the black and white comic market killed this series (like so many others), but Night-Realm would unexpectedly return a couple of years later with a new hero: Nathan Impaler.

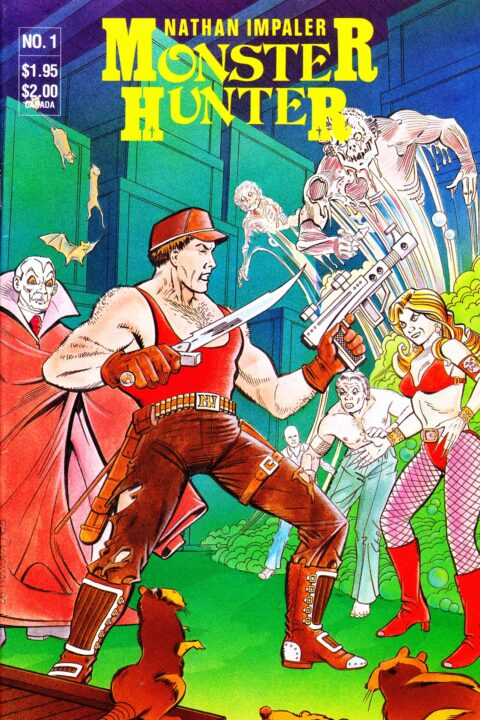

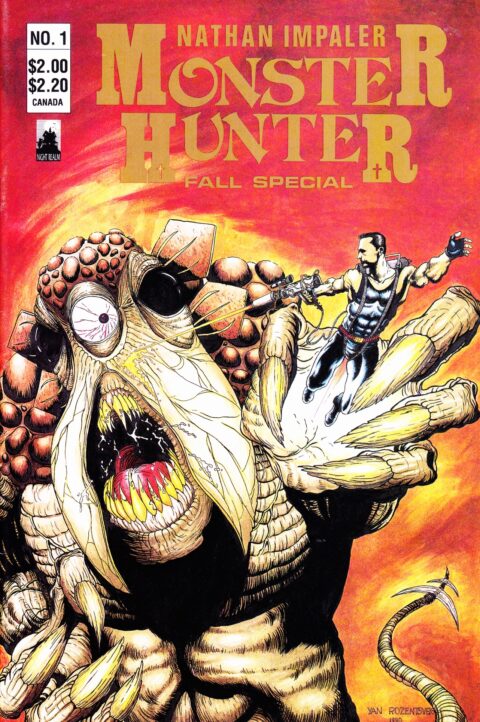

1990 saw the return of Night-Realm and the debut of Nathan Impaler, Monster Hunter. True to form, Diana’s return to comics began by lamenting the collapse of the market and blaming the demise of The Synthetic Assassin on bad art. He also blamed his lack of success on his inability to include advertisements in his comics (with only a couple of other comics featuring ads in The Synthetic Assassin). Nathan Impaler, we are led to believe, will be better.

Indeed, the first issue of Nathan Impaler, Monster Hunter is a major improvement over The Synthetic Assassin. There are advertisements and the artwork is better. With the new series, Diana ended up employing professional artist Ron Kasman to do the cover for the first issue (he also contributed to the “Werewolf Special”), while up-and-comer Yan Rozentsveig (who was associated with Tick Tock Tom) contributed much of the interior artwork on the series.

The end result is that the Nathan Impaler books are much better in terms of quality than their predecessor. Unfortunately, the series faced a different problem: Diana was unable to release the comic on schedule and ended up releasing the second and third issues of the comic as specials in 1991 and 1993. The series never took off and was abandoned before a third special could be released.

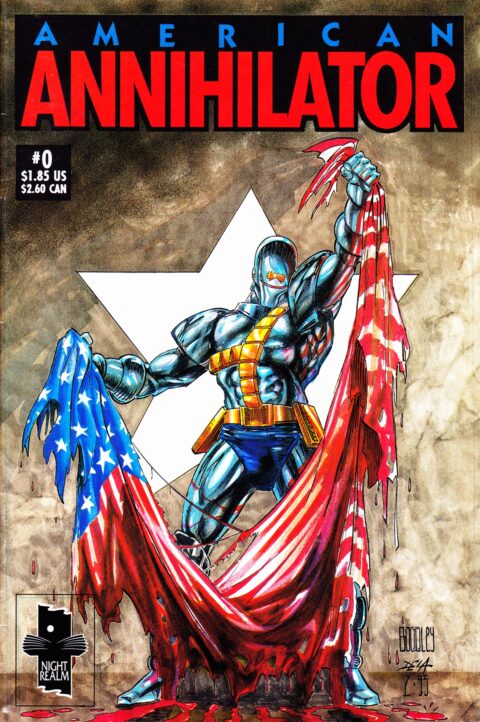

Surprisingly, Diana was not ready to give up. Instead, he brought Night-Realm back from the dead for a final time in 1995 with two new series (which would only last one issue each): American Annihilator and Blood Masters. Ron Kasman would continue working for the company on American Annihilator, which brought back the Synthetic Assassin as a secondary character and also tied itself to the world of Nathan Impaler. The comic was intended to bridge the gap between the earlier series while engaging in a bit of world-building for the Night-Realm universe.

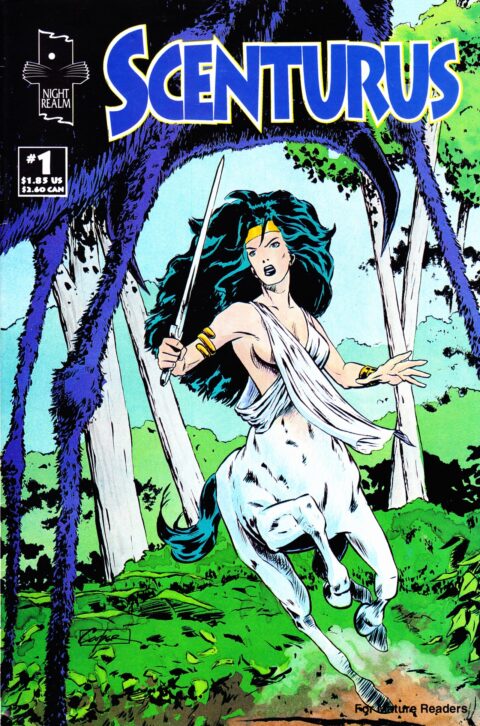

The final two comics published by Night-Realm would be released in 1996: Scenturus # 1 and 2. The series follows the adventures of a female centaur and a band of female warriors fighting monsters. The artwork was by another relatively unknown new artist, Frank Milkovich, with Scott Cooper providing the cover art for the first issue.

The third and final iteration of Night-Realm offers a glimpse at what could have been a really interesting series of comic publications. The four new comics escape the trappings of the two previous series and include quality artwork and narratives. Unfortunately for Fred Diana, he was re-entering the industry just as it was experiencing its second (and this time nearly total) collapse in less than a decade. Night-Realm was one of the many casualties of the great comic crash of the mid-1990s that nearly decimated everything by 1996. It was over and Night-Realm would never reappear again in any form (at least that I am aware of).

Ultimately, Night-Realm and the works of Fred Diana and Gordon Chin inhabit this strange and unfortunate space as a company that began as an attempt to take advantage of an already collapsing black and white comic market. However, their poor-quality product was, ironically, an example of the same problems that Diana complained about in his introductions of each issue of The Synthetic Assassin. They seemed to learn from these early mistakes with their 1990 relaunch by offering a better-quality product, only to fail to stick to their publishing schedule, alienating their audience in a very competitive market. By the time that Night-Realm had corrected its early problems and tried to reinvent itself for a third time, it finally had a quality product on offer, but the entire industry was crashing. Night-Realm learned from its mistakes, but returned at the worst possible time and slipped into the realm of ultra-obscure Canadian comics. It was too little, too late.

If you are interested in collecting comics published by Night-Realm, rest assured that they are easier to find if you are in Canada than what current eBay prices may suggest. I have come across all of these books in discount bins in the past, but only purchased copies of The Synthetic Assassin because I tend to pass on purchasing Canadian comics that are not part of the Canadian Silver Age. In retrospect, I wish that I had purchased copies of these books when I had the chance, as the pandemic has resulted in me making far fewer trips to comic books stores across Atlantic Canada than I used to. That said, in my experience issues of The Synthetic Assassin are much easier to find than issues of the Nathan Impaler books or the comics from 1995-1996. A patient collector should be able to ferret these out without having to break the bank.

I will continue my examination of poorly made amateur black and white Canadian Silver Age comics next month with Hell for Leather. See you then!

Hey brian

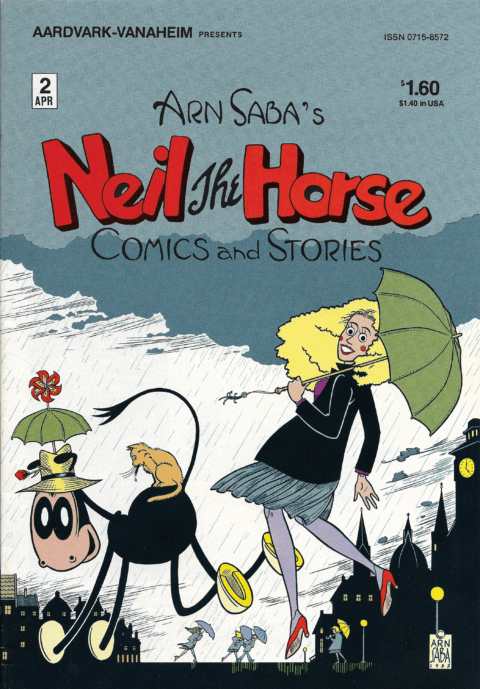

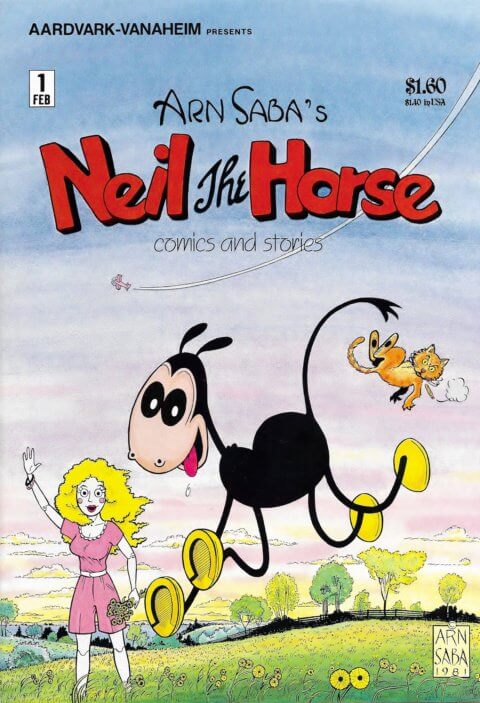

It’s nice to see that you have been referencing Bob MacMillan’s Encyclopedia of Canadian Animation, Cartooning and Illustration. Bob’s work in this field has been invaluable and he has left a wonderful legacy for future generations of Canadian comics fans, and it doesn’t hurt that he is one of the nicest people you can ever imagine meeting. I felt genuinely privileged to be included in his encyclopedia and his friendship has been one of the highlights of my brief comics career..

Hi mel, I agree that Bob’s website is an excellent resource. People who are interested in the history of Canadian comics, cartooning and animation should definitely check out his encyclopedia.

I echo Mel’s assertion and sentiment. Bob is constantly amending and adding to his online treasury of Canadian comics and cartooning information. You can find it here: https://canadianaci.ca/encyclopedia1/ . Just make an entry into the search box and you’ll be pleasantly surprised. Keep these columns coming, brian and we’ll have to get you on board for our second online Canadian Comics Conference this year.

Brian, it was interesting that this reflects so much of what went wrong in those two eras of independent publishing. Why publish something that you have to apologize for it from the outset? But at least they were aware of its shortcomings, which seems better than so many people were. Just like the “crudzines” in the 1960s and early 1970s, so many wanna-be publishers let their egos get in the way of critical self-evaluation. A publisher told me once, Tim Underwood in fact, better to bring out a book (in this case, we’re talking books but the same thing applies) late, than publish something you will not be proud of or happy with. I once accepted a poorly printed issue of The First Kingdom, with a lovely Steranko coloring job on the cover, that the printer just destroyed with bad color registration. I so wish I’d rejected it, as I have to live with it to this day, since it was never reprinted.

Sadly, your guys had problems with both quality AND scheduling, two strikes you are OUT.

I got out of distribution in mid-1988, when I sold out to Diamond, in the.midst of that first crisis, the b&w glut. I am keenly aware that we, as a distributor and as a retailer also, were tying up too much money in unsold books…and I was not wildly speculating.We may have been overordering ourselves to some extent, to have books for reorders from stores, but there were so many titles, it was easy to get carried away if you didn’t keep inventory control tight, tight, tight, a lesson only learned in retrospect.

But the larger problem was stores themselves who had over ordered, then could not pay their bills. It takes a while for that to percolate up the the publisher, who things he has a successful title with issue #1 or #2, but then the floor falls out on him when stores run out of money and distributors run out of patience on late-paying stores.

This all came very close to bankrupting me in 1987 to mid-1988, while I was in the process of selling my distribution part of my business to Diamond; so many comic stores were run by folks who had no concept of financial control. I’ve read that we went from 10,000 comic shops to 3000 somewhere in that 1988 to mid-1990s time period. I don’t know how true those numbers are, but they are probably indicative of the drop in outlets for comics. The non-sports card frenzy also added to everyone’s problems, since the same speculator issues came up there. Publishers were cranking out less and less appealing cards and variants that eventually overwhelmed the market.

So it wasn’t just Fan speculators, it was also comic shops speculating with money they didn’t have, filling up those long white boxes with crap, and expensive crap, as cover prices crept up also. The market was so fragile by then, all it took was Marvel to pull their distribution away from the, at the time, 10 or 15 comic distributors, to have us end up where we are today, with just one giant and relatively inefficient distributor, Diamond. Well, now three, since they’ve lost Marvel and DC now.

Thanks for posting this link, Ivan. Folks, definitely check out Bob’s website if you haven’t already. Fingers crossed that I will be able to participate in the Canadian Comics Conference this year.

You make some excellent points here, Bud. It is easy to point towards fan speculators/investment collectors specifically as the primary cause of a market bubble. Yet, it is important to remember that they are only one part of a system that enables a bubble to occur. As you suggest, in this case, distributors, publishers, creators and comic shops were all culpable and played a role in these two collapses in the comics market.

Although the factors may be different for the creation of any given collectibles bubble, I think that this same logic applies when any collector market collapses. I can think of several examples, from sports cards in the early 1990s to Beanie Babies in the late 1990s and even DVDs and rare movies in the early 2010s. As soon as the shops pumping up the product can’t pay the bills, it’s over. I think that video games are reaching this point now (especially because of the Wata grading racket). I also sometimes worry that comic books are approaching this level again for a variety of reasons. At least most comic shops and collectibles stores are a lot more diversified than they once were, making it easier to swallow a downturn in a particular collectibles market.

Sometimes collector markets are entirely manufactured by people who are only looking to make money through speculation. A good recent rabbit hole that is worth looking at is the graded VHS market that popped up less than a year ago. Stay away from graded VHS, folks: it’s a scam.

Of course, I approach these issues from my own position as a dealer, collector and researcher and all of this influences how I approach the subject (as well as what I buy to resell and what collectibles markets I focus on). Your experience as a distributor and publisher makes your understanding of this subject regarding comic books invaluable because of it being a relatively unique position combined with lived experience. Pointing to comic shops in particular as being culpable is this makes perfect sense.

Bringing this discussion back to Night-Realm, there are so many poor quality comics from this era and The Synthetic Assassin is not unique. Just wait until you see Hell for Leather next month!

This amateur Black and white independent comic books era seems like a great training ground for budding artists inkers and writers and such Brian. Was this so? Did any achieve long term success? Thanks for the interesting work.

This is a great question, Dave. Many Canadian creators who would go on to become quite successful contributed to black and white comics during this era. Most of the bigger Canadian names (such as Dale Keown, Seth and Chester Brown) worked for the major independent Canadian companies of the time (such as Aircel and Vortex). That said, arguably the best-known Canadian comic artist from the 1990s, Todd McFarlane, completely side-stepped the black and white era.

Many Canadian creators who worked in black and white comics stayed in comics in some capacity in the decades that followed, even if they did not become well known after the 1980s ended. Just as many drifted into obscurity. In some cases, creators contributed to one comic or series and disappeared entirely. It’s really a mixed bag. In the case of Night-Realm, Ron Kasman had already contributed to numerous black and white comics in Canada (such as Quadrant) and continues to work in comics today. His efforts would culminate with the release the very well-received and highly recommended The Tower of Comic Book Freaks half a decade ago.

Yan Rozentsveig would go on to work on Tic Toc Tom in the mid-1990s, but that series did not survive the collapse of the comic market either. I am not sure if he continued in comics afterwards. As far as I can tell, the majority of people who worked as part of the three iterations of Night-Realm left comics altogether.