In my last article, I discussed the ritualistic nature of comic book collecting and participating in comic book fandom. I then outlined the challenges facing the industry in terms of increasing a readership that has been diminishing over the last twenty years. This article will discuss the form and function of the iPad as an eReader. In addition, the implications of the digital distribution of comics will be identified and analyzed to determine if comic collectors and fans would be willing to change how they view and collect comics.

The iPad as an E-Reader

The iPad – like the iPod and iPhone before it – strives to make the consumption of a variety of media and entertainment content more pleasurable than it would be on a different, often smaller, portable media device (like an iPod, iPhone, or other portable media device like a PSP or smart phone). It was, as Lowe (2010) argues, “designed solely for the enjoyment of digitally distributed media and software.” However, the iPad device itself is just hardware. It is the software – called Apps or application software – that will differentiate the iPad from all of the other devices on the market. Created by both Apple and third-party creators, Apps amplify the hardware advantages of the iPad, such as its large colour screen (Heseldahl, 2010).

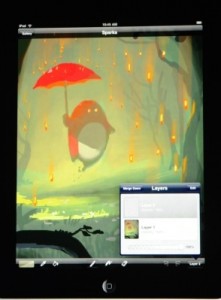

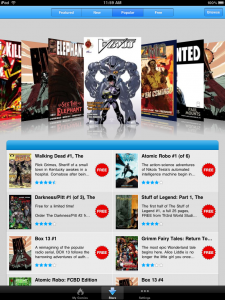

It is through its software applications that Apple is planning to release a number of comic book readers for the iPad. Some readers will be provided by the comic book publishers themselves. Others however, will come from third-party companies who seek to integrate the different publisher platforms in order to create an all-in-one reader for comic book fans. It remains to be seen, however, if the App Store will result in “incremental revenue from a larger, non-traditional audience” (Weitzner, qtd. In Griffin, 2010). The iPad’s use of pixel doubling – whereby Apps sized for the smaller iPhone and iPod Touch are resized to fit the screen size of the iPad – and cross platform functionality, will run almost every one of the over 150,000 Apps currently hosted at the App Store. Furthermore, by the time the iPad launched in the United States, there were more than 1,000 iPad-specific Apps available for purchase or free download (Davies, 2009).

Reading comics using the iPad and its Apps will be attractive to non-traditional audiences are non-comic book fans and collectors who find purchasing printed comics too expensive, too difficult, or too cumbersome. As the iPad offers the distribution of comic books wirelessly (or over the 3G network), for less than they cost at a retail store, and do not take up any physical space, these difficulties are eliminated. Furthermore, individuals who find conventions and comic book stores exclusionary and unwelcoming – such as women and novice readers – would be able to access the content with little trouble. Furthermore, individuals who used to read comics but who stopped reading comics may be enticed to return to the medium. Ultimately, “publishers hope new digital versions of their titles can turn comics into mass-market entertainment, not just artefacts for collectors” (MacMillian, 2010).

According to the Consumer Electronics Association, 2.2 million e-readers were sold in the United States in 2009. This number is expected to increase to 5 million in 2010 (Betancourt, 2010). As an e-reader, the portability of the iPad is one of its strengths (Griffin, 2010). Another strength is located in its colour display – other e-readers on the market are only in greyscale. Finally, the iPad is not just an e-reader, but is a multimedia and productivity device. Therefore, the strength of the iPad comes from the abilities of its manufacturer, Apple, to “seamlessly deliver a wide range of content to the consumer” and predicts that the iPad “will boost the popularity of e-books and get more people reading”, making it a force to be reckoned with when it faces off against other e-readers currently on the market (Young, qtd. Reid & Milliot, 2010). This popularity of the iPad as an e-reader is also expected to increase the popularity of comic books and ultimately increase readership.

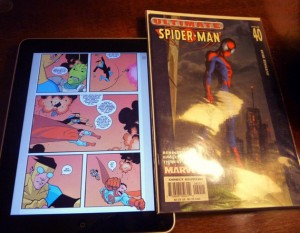

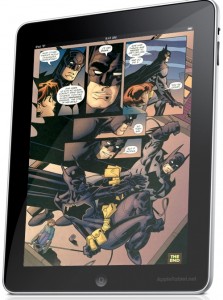

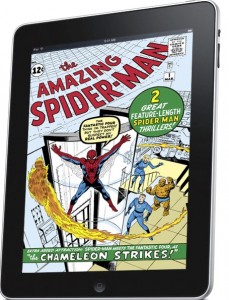

In terms using the iPad as a comic book reader, the device’s portability and its large colour display are two of the key benefits that make it attractive. To begin with, there is no need to physically store either the collected editions of individual issues (trade paperbacks) or the individual issues. If everything is stored digitally, individuals who do not have the space or the desire to store hardcopies can read comics. Furthermore, individuals will be able to carry around with them their entire collection in digital format, something that they would be unable to do if they were to try to attempt to do so with hardcopies (George, 2010). In addition, the size of the iPad’s display screen is 9.7-inches – which is very close to the 10.25-inches that standard comic books are. Furthermore, the display is in colour. Unlike smaller readers, such as the iPhone (which also boasts a colour display), where the affect of the art is diminished and users have found comics difficult to read on the small screen (Kuehlein, 2010). Furthermore, as non-colour readers cannot accurately convey the affect of the art, no publishers have yet offered digital comics on them (St. Louis, 2009). Finally, the price of the comics – which is roughly half of what hardcopy comic books cost – consumers will be more likely to buy more comics, since they will be able to get more for the same amount of money. Therefore, the iPad is “a pioneer for digital comics that has finally solved the key issues of distribution, price, and portability, while preserving the medium as best as possible” (George, 2010).

In terms using the iPad as a comic book reader, the device’s portability and its large colour display are two of the key benefits that make it attractive. To begin with, there is no need to physically store either the collected editions of individual issues (trade paperbacks) or the individual issues. If everything is stored digitally, individuals who do not have the space or the desire to store hardcopies can read comics. Furthermore, individuals will be able to carry around with them their entire collection in digital format, something that they would be unable to do if they were to try to attempt to do so with hardcopies (George, 2010). In addition, the size of the iPad’s display screen is 9.7-inches – which is very close to the 10.25-inches that standard comic books are. Furthermore, the display is in colour. Unlike smaller readers, such as the iPhone (which also boasts a colour display), where the affect of the art is diminished and users have found comics difficult to read on the small screen (Kuehlein, 2010). Furthermore, as non-colour readers cannot accurately convey the affect of the art, no publishers have yet offered digital comics on them (St. Louis, 2009). Finally, the price of the comics – which is roughly half of what hardcopy comic books cost – consumers will be more likely to buy more comics, since they will be able to get more for the same amount of money. Therefore, the iPad is “a pioneer for digital comics that has finally solved the key issues of distribution, price, and portability, while preserving the medium as best as possible” (George, 2010).

It is not just these aspects that make the iPad an attractive to comic book fans and collectors. Since the typical comic book consumer – at least for superhero comics – is male, with disposable income and typically a technophile, these individuals will likely be early adopters of new technology, like the iPad. In general, fandom participation involves both discussion of the object of adoration and other informal social interactions online. Fans are brought together by their mutual adoration of a popular culture text but often form friendships with other fans that they come in contact with (Jenkins, 1992). Given that most comic book fans and collectors participate in the fandom online, usually through blogging communities and message board posts, their positive reviews may influence other people to purchase the iPad as well. Word-of-Mouth communication (WoM) is the process by which “product information is conveyed by individuals to other individuals on an informal basis” (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, p. 322). WoM is very influential because it is viewed as more trustworthy and reliable than other marketing initiatives, especially when there is a close relationship between the parties. Furthermore, the power and persuasiveness of WoM is reinforced by additional social pressures to conform – especially if the person who recommends a product or service has more knowledge about the product or service being recommended, greater social status and/or power – for example, if they were fandom insiders – than the other. WoM works through repetition – the more positive reviews that an individual hears, the more likely he/she is to embrace the product or service being recommended (Solomon, Zaichkowsky, & Polegato, 2008, pp. 322-324).

Web 2.0 and the iPad

Responsible for further empowering consumer choices as well as influencing consumer behaviour, the phenomenon known as Web 2.0 is defined by Constantinides and Fountain (2008) as

a collection of open-source, interactive and user-controlled online applications expanding experiences, knowledge and market power of the users as participants in business and social processes. Web 2.0 applications support the creation of informal users’ networks facilitating the flow of ideas and knowledge by allowing the efficient generation, dissemination, sharing, and editing/refining of informational content. (pp. 232-233)

The key differentiation is that the user is both consumer and supplier. The App Store is set up so that the user is usually just a consumer of the App. However, this is not the only way in which users can access Apps. Consumers can also use web-site based Apps. These Apps are accessed over the internet – opposed to being installed on the device – and are either hosted or supported by an internet browser. Unlike installed Apps that are purchased at the App Store, web-based Apps can be updated and maintained easily, eliminating the need to repurchase and/or reinstall the website. Furthermore, web-based Apps are not as difficult to create as those that are installed on the iPad (McClellen, 2010).

In January 2010, only 20% of mobile subscribers in the United States downloaded an App from the App Store. This demonstrates that Apps that are hosted at the App Store and are downloaded cannot “reach the entire population unless it is reformatted a number of times” (Patel, 2010). Therefore, these simple, easy-to-use web-Apps Apps can offer its users highly personalized content and “emphasizes the trend towards openness and technology democratization and introduces new forms of participation based on decentralization and user-generated content” (Constantinides & Fountain, 2008, 242). In other words, “unlike most mobile devices, which are personal” the iPad will “instead be shared” (Morrissey, 2010).

In January 2010, only 20% of mobile subscribers in the United States downloaded an App from the App Store. This demonstrates that Apps that are hosted at the App Store and are downloaded cannot “reach the entire population unless it is reformatted a number of times” (Patel, 2010). Therefore, these simple, easy-to-use web-Apps Apps can offer its users highly personalized content and “emphasizes the trend towards openness and technology democratization and introduces new forms of participation based on decentralization and user-generated content” (Constantinides & Fountain, 2008, 242). In other words, “unlike most mobile devices, which are personal” the iPad will “instead be shared” (Morrissey, 2010).

Furthermore, whether the App is installed on the device or web-based, Apps have the potential to meet the needs of a “previously untapped” market of “individual, ‘unsegmented’ consumers with very specific interests and demand for low-volume, customized products and services” (Constantinides & Fountain, 2008, p. 237). Due to the dwindling sales that the comic book industry faces, Apps that would turn the iPad into a comic book reader and have the opportunity to serve current readers and simultaneously attract new ones. These “niche consumers can create substantial aggregated demand for products and services not belonging to the mainstream or ‘hit’ categories” (Constantinides & Fountain, 2008, p. 237). By tapping into digital distribution channels, comic book publishers can potentially serve a larger, global audience than they could using the direct market, especially since the number of comic book stores have dropped significantly since the 1990s. In other words, by using Apps to transform the iPad into a comic book reader, the reach of comic book publishers is increased as they no longer need to depend on physical stores to distribute their products. This results in a cost saving in terms of printing and distribution costs on the part of the publisher (George, 2010).

Unlike other e-readers, iPad users will be able to download Apps to read other formats found on other e-readers, including Amazon’s Kindle and Barnes and Noble’s Nook – both of which are proprietary formats. As an e-reader, the iPad’s native format is EPUB and is the format that Apple’s iBookstore – similar to iTunes – will sell its e-books. EPUB is a “free and open format, very easy to use, can receive DRM, and is designed to be reflowable (allowing it to fit any device as it will resize to fit the dimensions available” (McClellan, 2010). Furthermore, the EPUB formats can be read by a number of different e-readers already on the market. Should individuals choose to not purchase an iPad – or if they have already purchased a reader – they can still purchase e-books from iBookstore. If they are satisfied with their purchases, when it comes time to purchase a new e-reader, they may choose to buy an iPad. In other words, users will be able to access e-books in other formats, in addition to those offered through iBookstore, increasing the size of the library available to individuals.

Proprietary e-reader formats and Apps – both of which are difficult to create and maintain – had the potential to create “a barrier” and facilitate the “creat[ion] of a class of middle-men merchants” who “were required to get your book out in the wild digitally” (McClelland, 2010). iPad’s use of the EPUB format is unique in that the format is exceptionally easy for the layperson to code and create, especially when it comes to creating e-books for comics. Even the more advanced features that are offered by the format – such as linking content to the web and creating a table of contents – are not outside the realm of the layperson to program. This opens up the possibilities for independent writer/artists and web comics producers to create e-book collections of their comics for sale. Without the need for expensive coding in order to create a comic e-book, the entire process is democratized as the entry barriers impeding independent comic creator participation are eliminated (McClellen, 2010).

Censorship at Apple’s App Store

In 2010, Apple’s App store began removing Apps (that had previously been approved for sale) that contained sexual content as the store had received complaints from a number of customers (Chen, 2010a). Chen (2010b; 2010c) also accused Apple of hypocrisy as some Apps that contained similar content – but were developed by large magazine publishing companies (such as Playboy, Sports Illustrated, and Maxim) were not censored. The lack of published guidelines when it comes to questionable content has resulted in an unequal application of these guidelines and may, in fact, alienate some users of the store and lead to them choosing not to adopt iPad technology, choosing to wait for another developer’s technology. On the one hand, this demonstrates the high levels of quality control and user protection that the App Store offers to its customers. On the other hand, the App Store’s lack of transparency when it comes to guidelines as to what kind of content can be deemed offensive and thus cannot be included in its Apps. As a result, App developers could begin to censor themselves, which will ultimately stifle creativity and innovation when it comes to the development of Apps (Chen, 2010c).

In 2010, Apple’s App store began removing Apps (that had previously been approved for sale) that contained sexual content as the store had received complaints from a number of customers (Chen, 2010a). Chen (2010b; 2010c) also accused Apple of hypocrisy as some Apps that contained similar content – but were developed by large magazine publishing companies (such as Playboy, Sports Illustrated, and Maxim) were not censored. The lack of published guidelines when it comes to questionable content has resulted in an unequal application of these guidelines and may, in fact, alienate some users of the store and lead to them choosing not to adopt iPad technology, choosing to wait for another developer’s technology. On the one hand, this demonstrates the high levels of quality control and user protection that the App Store offers to its customers. On the other hand, the App Store’s lack of transparency when it comes to guidelines as to what kind of content can be deemed offensive and thus cannot be included in its Apps. As a result, App developers could begin to censor themselves, which will ultimately stifle creativity and innovation when it comes to the development of Apps (Chen, 2010c).

Chen (2010b) and other critics have likened Apple’s App Store censorship to that of Wal-Mart’s refusal to sell of CDs that had parental advisory warnings. In fact, as the largest retailer of music, Wal-Mart was able to exert considerable amounts of pressure over the musicians and music producers, “suggest[ing] that artists change lyrics and CD covers that it deems objectionable” (Chen, 2010c). In other words, unless Apple finds a different way of distributing its Apps – or the content used by its Apps – either by refiguring the iTunes music store to include printed material (books, magazine, comic books, newspapers) or by allowing iPad users to purchase these Apps from outside the App Store, then these products may similarly be censored by the Apple.

In the case of Wal-Mart, censorship has become motivated by economics. Therefore, if the iPad is as successful a distribution channel for comic books and other media as it was for music, then publishers cannot afford to not use it as a distribution channel. Therefore, they will make whatever changes that Apple dictates in order to keep its place in the App store. Furthermore, If content continues to be censored through the app store, Chen (2010b) predicts that Apple will not only “drive loyal customers away” but also App developers to other similar tablet computers.

Digital Comics: Expensive and no Freedom of Choice

Marvel Comics has been criticized for selling its digital content as a subscription, locking individuals into a contract that removes their freedom of choice when it comes to choosing different monthly titles every time. Furthermore, Marvel has also been accused of price gouging. Comic book consumers state that the $1.99 cost of comics is excessive, especially in terms of its sale of non-recent or back issue books. While the cost of new comics is less than their printed counterparts – which range in cost from $3 to $5 due to increased production and shipping costs – the critique of newly published books is that they cannot be shared. Unlike the iTunes store, where the consumer can authorize up to five different computers to play their music, the Marvel App on the iPad disallows this sharing function. In addition, many consumers say that digital comics should be cheaper than $1.99 as there are no costs associated with paper, printing, or distribution. Furthermore, the prices of back issues are also $1.99, which is more than most stores charge for their back issues (George, 2010; Meadows, 2010).

Marvel Comics has been criticized for selling its digital content as a subscription, locking individuals into a contract that removes their freedom of choice when it comes to choosing different monthly titles every time. Furthermore, Marvel has also been accused of price gouging. Comic book consumers state that the $1.99 cost of comics is excessive, especially in terms of its sale of non-recent or back issue books. While the cost of new comics is less than their printed counterparts – which range in cost from $3 to $5 due to increased production and shipping costs – the critique of newly published books is that they cannot be shared. Unlike the iTunes store, where the consumer can authorize up to five different computers to play their music, the Marvel App on the iPad disallows this sharing function. In addition, many consumers say that digital comics should be cheaper than $1.99 as there are no costs associated with paper, printing, or distribution. Furthermore, the prices of back issues are also $1.99, which is more than most stores charge for their back issues (George, 2010; Meadows, 2010).

Ritualism versus Digital Consumption

Wolk (2010) notes that by using a direct market distribution channel, the comic book industry has “constructed their whole business model on ‘collectability’, which obviously disappears the moment you’ve got digital reproduction” (qtd. in Ha, 2010). For example, Phegley (2010) states that the chief benefits of the iPad come from the centralization and collection of a portable digital comics library. Furthermore, digitization would allow to easily navigation among storylines and characters, including linked text to articles that detail the character biographies, which is helpful given that the two largest comic book publishers both have over 50 years of continuity. Furthermore, this may be a cost effective way for more people to collect the older, rarer, and more expensive early issues of a series. Instead of paying $1.5 million for a one of the less than hundred copies still remaining for Action Comics #1 (June 1938), which is the first appearance of Superman, digital readers can supply the same comic for around a $2-$4 price point (Melrose, 2010). This increases accessibility and availability of comic books as the consumption of comic books texts as an individual pursuit. This will increase the likelihood that non-comic book fans and collectors will have decreased barriers of entry to stories that are often entrenched in decades of continuity.

Wolk (2010) notes that by using a direct market distribution channel, the comic book industry has “constructed their whole business model on ‘collectability’, which obviously disappears the moment you’ve got digital reproduction” (qtd. in Ha, 2010). For example, Phegley (2010) states that the chief benefits of the iPad come from the centralization and collection of a portable digital comics library. Furthermore, digitization would allow to easily navigation among storylines and characters, including linked text to articles that detail the character biographies, which is helpful given that the two largest comic book publishers both have over 50 years of continuity. Furthermore, this may be a cost effective way for more people to collect the older, rarer, and more expensive early issues of a series. Instead of paying $1.5 million for a one of the less than hundred copies still remaining for Action Comics #1 (June 1938), which is the first appearance of Superman, digital readers can supply the same comic for around a $2-$4 price point (Melrose, 2010). This increases accessibility and availability of comic books as the consumption of comic books texts as an individual pursuit. This will increase the likelihood that non-comic book fans and collectors will have decreased barriers of entry to stories that are often entrenched in decades of continuity.

Martinelli (2010) reports that publishers of comic books predict that, despite the portability and potential for interconnectivity among these texts that there will still be a market for paper or hardcopy editions of the individual issues. On the one hand, this predicts that there will be very little cannibalization of the direct market from the digital market. However, on the other hand, this does nothing to help lower production and shipping costs for the publisher. Therefore, as a result of these increasing costs, the ultimate price of the final product increases for the customer. While comic books have shown remarkable resilience in terms of the economic downturn, the increasing costs will likely result in declining sales as customers will stop collected as many books as they do. Simply stated, once prices top out for each individual collector, he/she will begin to cut titles from his/her weekly purchase list, becoming more discerning when it comes to the titles they purchase. At this time, these customers may adopt digital content for comics that they enjoy reading but can no longer afford to collect, and may move to digital comics for the titles they can no longer afford in print. However, should the digital distribution channel fail to attract and retain these consumers, these fans and collectors may either stop collecting these titles entirely or resort to illegal file sharing programs to get copies of these comics for free.

Other Challenges Facing Publishers

Furthermore, the use of the iPad as an e-reader has the potential to cannibalize sales that would have gone to comic book specialty stores, a distribution channel that has already dwindled over the last twenty years. Given the shrinking and fragile nature of the direct market distribution channel, if there is any failure within that channel – whether at the level of the distributor, Diamond Comics, or at the level of the specialty retailer – then the whole system might fail. As a result, the industry’s “target audience is now fractured with some digital and many non-digital adopters left out in the cold. It’s a burning the candle at both ends possibility or paradigm shift for the comic industry and both companies are unsure of how they want to proceed” (Warren, 2010). Therefore, publishers must be conscious as to the long-term implications of their plans when it comes to this new distribution channel. Publishers should strive to keep a balance between maintaining its current practices with regard to print while simultaneously attracting that same audience and new readers to its digital offerings.

However, this assertion that cannibalization is an aforementioned conclusion of expanding into digital distribution is not necessarily the case. Despite the closure of stores and sales figures dropping over the last twenty years, the sale of comic books has remained fairly constant over the last five or so years, despite the recent economic downturn. In fact, sales of “comic books are doing fine” even though “the publishing industry is in a freefall” due to the economic downturn (Anderman, 2009). The robust survivability of this textual form in times of economic hardship – despite the increasing cost of comics – indicates its reified status for those who collect it.

St. Louis (2009) argues that Apps for the iPad and the iPhone are “platform-centric” and that this may not accurately reflect the actual demographics of those who actually want to utilize the digital distribution channel to get their comic content. If any technology is to succeed, in other words, it cannot limit the distribution market to only those who have the platform. Therefore, “Any solution based on one platform, no matter how popular it is in the public, has to be popular with that segment of the public that buys and reads comic books” (St. Louis, 2009). While the EPUB format of the iPad resolves some of this concern – as these comics can be read on other readers – one of the ways in which publishers can increase the availability of their digital content is to release it in a format that can be read across platforms. They can do this by simply using the EPUB format or by providing Apps or programs for their iPad content to be read on other devices to maximize its adoptability within the market of comic book consumers.

St. Louis (2009) argues that Apps for the iPad and the iPhone are “platform-centric” and that this may not accurately reflect the actual demographics of those who actually want to utilize the digital distribution channel to get their comic content. If any technology is to succeed, in other words, it cannot limit the distribution market to only those who have the platform. Therefore, “Any solution based on one platform, no matter how popular it is in the public, has to be popular with that segment of the public that buys and reads comic books” (St. Louis, 2009). While the EPUB format of the iPad resolves some of this concern – as these comics can be read on other readers – one of the ways in which publishers can increase the availability of their digital content is to release it in a format that can be read across platforms. They can do this by simply using the EPUB format or by providing Apps or programs for their iPad content to be read on other devices to maximize its adoptability within the market of comic book consumers.

Ives (2010), among others, note that publishers will have to create content that “allows interactivity and other digital capabilities” in order to attract consumers to pay for content that they could find on the internet for free (see also Jaroslovsky, 2010). In other words, content cannot just be digitized for use on the iPad. Instead it “needs to be richer, offer more user control and interaction, and has to let the user manipulate it in a way that it becomes highly individualized” (Betancourt, 2010). If they offer enough of this bonus content, they may entice fans and collectors who will come to collect both the print and the digital versions of books. However, publishers need to accurately predict what kind of bonus content – such as interviews with the creators, creator podcasts, and sketches – will be most attractive while remaining the most cost efficient. Above all, this content must be original and “created to take advantage of the new format” (St. Louis, 2009). In other words, digital content offerings cannot simply be scans of the printed comic book – which may not be the best way to present the material on the iPad. Instead, it should play to the strengths of the iPad and provide original content unavailable in other forms of delivery. By taking advantage of the uniqueness of the iPad as a device, consumers will embrace digital content as it is “easier to read or more appealing” to the consumer than other forms of distribution.

One of the lures of digital distribution is the portability and lower price of the comic compared to its print counterpart. If the bonus material inflates the price, then this might increase current fans and collectors to purchase the digital versions in addition to (or even in lieu of) the printed content. However, a price increase may make the digital content too expensive for the non-traditional reader. In the best case, publishers simply increase their sales of digital content to pre-existing comic book fans and collectors without attracting new readers. In the worst case, print consumers move to exclusively digital content, effectively driving the direct market out of business and alienating the possibility of attracting new readers.

Conclusion

On the one hand, digital distribution will make it easier for casual readers and non-collectors to get access and consume the media. Overcoming barriers to access – whether it is by making digital content more easily acceptable, providing a more portable product at a lower price, or by providing informational links within the digital content to situate the character and story in terms of a vast and often confusing continuity – will increase new readers engagement with this form of popular culture (George, 2010). Despite this potential, this study has also identified a number of challenges and postulated possible solutions that absolutely must be addressed before the iPad is able to preserve – and perhaps even grow – the comic book industry as it currently stands.

On the other hand, current comic book fans and collectors could never replace the physical collection of comic books with the iPad. Fans and collectors are so entrenched in the rituals and social interaction related to collecting comic books and participating in comic book fandom that these cannot be easily replaced with digital collections. As a sacred or fetishistic object, the comic book, for collectors, is a part of an interconnected ritual through which he/she sets out and acquires new objects to put into his/her collection each time he/she goes to the comic book store. The self-concept, identity, and behaviour that a collector engages in when he/she acquires a new object for his/her collection are simply not addressed by digital distribution as it currently stands.

In other words, for fans and collectors consuming comic books – searching out, purchasing, reading, and then adding them to their collections – is not only about entertainment. Rather it is both a reinforcement and an enactment of an adopted identity that is so firmly entrenched in non-economic benefits that the potential digital distribution channels that are opened by the utilization of the iPad has yet to address. For one thing, as Brown (1997) notes, the collector and fan “construct a meaningful sense of self” (p. 13) because fan activities and fan communities “is almost exclusively centered around a physical possessable text” (p. 22). It occurs exclusively in the possession of a physical comic book, the tactile sensations associated with such objects, as well as the memories that those two things evoke within the collector or fan. Moving to a digital collection of content, therefore, would be impossible as it removes the material artefact from the equation. The physical collection of the fetish object is much different from the digital collection of one. This is not to say that fans and collectors will not embrace the iPad as a portable way in which to consume their comics. However, it is impossible for the iPad to replace the psycho-social benefits ascribed to the physical collection of comic books.

References and General Bibliography

Allen, R. J. (2006, July 21). From comic book to graphic novel: Why are graphic novels so popular?

Anderman, J. (2009, November 14). All new adventures! The Boston Globe.

Bacon-Smith, C. (1992). Enterprising women: Television fandom and the creation of popular myth. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bacon-Smith, C. (Ed.) (2000). Science fiction culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Baig, E. C. (2010, April 1). Verdict is in on Apple iPad: It’s a winner.

Betancourt, L. (2010, February 18). Can e-readers and tablets save the news?

Bongco, M. (2000). Reading comics: Language, culture, and the concept of the superhero in comic books. New York, NY: Garland Publishing, Inc.

Brown, J. A. (1997, Spring). Comic book fandom and cultural capital. Journal of Popular Culture, 30(4), 13-31.

Bullas, J. (2010, March 14). What 3 industries is the Apple iPad threatening to decimate?

Chen, B. X. (2010a, February 19). Apple removes porn Apps from App Store.

Chen, B. X. (2010b, February 25). iPad Apps could put Apple in charge of the news.

Chen, B. X. (2010c, April 26). A call for transparency in Apple’s App Store.

Constantinides, E., & Fountain, S. J. (2008, January). Web 2.0: Conceptual foundations and marketing issues. Journal of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice, 9(3), 231-244.

Davies, C. (2009, November 5). Apple App Store stuffed with over 100,000 applications.

DiBello, J. (2008, August 15). A serious note.

D’Orazio, V. (2008, January 24). The demographics of the mainstream comic book reader [Blog posting].

Draper Carlson, J. (2008, January 24). Superhero comic readers still mostly male [Blog posting].

Dumenco, S. (2010, April 5). Just how much saving of the media does the iPad need to do, actually?

Fost, D. (1991, May). Comics age with the Baby Boom: Marketing comic books to members of the Baby-Boom generation. American Demographics, 13(5), 16.

Fusanosuke, N. (2003). Japanese manga: Its expression and popularity. Asian/Pacific Book Development (ABD) Magazine, 34(1), 3-5.

Garrity, S. (2007, November). The Gail Simone interview. The Comics Journal, 296, 68-91.

George, R. (2010, April 7). How the iPad can change the comics industry.

Griffin, M. (2010, February 8). Business publishers see iPad potential. B to B, 95(2), 1-24.

Ha, P. (2010, February 10). A comic pundit’s thoughts on the iPad and digital comics.

Hebdige, D. (1984) Subculture: The meaning of style. New York, NY: Methuen and Company, Ltd.

Hesseldahl, A. (2010, February 5). Apple’s hard iPad sell.

Harris, C. & Alexander, A. (Eds.) (1998). Theorizing fandom: Fans, subculture, and identity. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, Inc.

Hills, M. (2002). Fan cultures. London, UK: Routledge.

Ives, N. (2010, April 5). Publishers experiment with iPad ad models. Advertising Age, 81(14), 2-17.

Jaroslovsky, R. (2010, February 4). An iPad in your pad? It’s up to the Apps.

Jenkins, H. (1992). Textual poachers: Television fans and participatory culture. New York, NY: Routledge.

Klaassen, A., & Lakin, M.. (2008, July). We get it: The iPhone’s big. App Store will make it bigger. Advertising Age, 79(27), 3,24.

Kuehlein, J. P. (2010, April 4). iPad to let comics turn page? Graphic stories haven’t been altered by digital culture so far. That may be about to change.

Lopes, P. (2006, September). Culture and stigma: Popular culture and the case of comic books. Sociological Forum, 27(3), 387-414.

Lowe, S. (2010, April 7). How the iPad can change the comics industry: The tech perspective.

McAllister, M. (2001). Ownership concentration in the U.S. comic book industry. In M. P. McAllister, E. H. Sewell Jr., and I. Gordan (Eds.) Comics and Ideology, pp. 15-38. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

MacDonald, H. (2007, February 23). Graphic novel sales hit $330 million in 2006.

Mackay, B. (2007, March 18). Hero deficit: Comic books in decline. The Toronto Star.

MacMillan, D. (2010, April 5). Comic book publishers plot comeback via Apple iPad. Retrieved from:

Martinelli, N. (2010, February 3). Holy heart failure! Comics await the iPad.

Masters, C. (2006, August 10). America is drawn to manga. Time.

McClellan, R. (2010, March 16). iPad, EPUB, Apps, and comics – Oh, my!

Meadows, C. (2010, April 12). Will the iPad save comics, destroy comic book shops, or increase comic book piracy?

Melrose, K. (2010, March 29). Superman back on top as Action Comics #1 sells for record $1.5 million.

(2010, March). Mobile apps on rise. Health Management Technology, 31(3), 8.

Morrissey, B. (2010, April 5). iPad changes everything?. Adweek, 51(14), 6.

Nyberg, A. K. (1998). Seal of approval: The history of the Comics Code. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

(2009, September 9). Paul Levitz no longer Publisher and President of DC Comics [Press release].

Patel, K. (2010, March 22). Little love for the mobile web in app-adoring world.

Phegley, K. (2009, December 31). Marvel and Disney: A done deal.

Phegley, K. (2010, January 27). The iPad and comics: What’s next?

Reid, C., & Milliot, J. (2010, February 1). Apple’s iPad invades Digital Book World. Publishers Weekly, 257(5), 4-5.

Sadighi, L. (2010, January 27). Apple’s iPad: Kindle killer?

Schiller, K. (2010, April 8). iPad already impacting.

Snell, J. (2010, January 28). iPad: Perfect for digital comics?

Solomon, M. R., Zaichkowsky, J. L., and Polegato, R. (2008). Consumer behaviour: Buying, having, and being (Custom edition for Ryerson University). Toronto, ON: Pearson Custom Publishing.

St. Louis, H. (2009, October 28). iPhone apps for comics are stupid.

St. Louis, H. (2009, October 31). Web comics: Rumoured Apple iTablet is second coming for comic book industry.

Thornton, S. (1996). Club cultures: Music, media, and subcultural capital. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Thorpe, V. (2009, March 22). Why women read more than men. The Observer.

Warren, K. (2010, January 28). The Apple iPad, comics, and you.

Witek, J. (1999). Comic books as history: The narrative art of Jack Johnson, Art Spiegelmen, and Harvey Pekar. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Wright, B. W. (2001). Comic book nation: The transformation of youth culture in America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Shelley Smarz is a comic book scholar and MBA Candidate at Ryerson University. She’s currently reading Carrie Fisher’s Wishful Drinking and enjoying it thoroughly (it’s HILARIOUS). She’s currently attempting to figure out how she can get an iPad on an HR Intern’s salary (without it resulting in her diet consisting of only ramen noodles and Kraft Dinner for the next two months).