The early 1970s was a magical time for Canadian comic books. After decades of scant output from the mid-1940s through the 1950s, the 1960s was dominated by the giveaway comics produced by Ganes Productions and Comic Page Features/Comic Book World. This started to change by the end of the 1960s, with comic creators experimenting across the country through myriad genres, albeit often in starts and stops. Vancouver, the Greater Toronto Area and Ottawa became hotbeds of English language comic book activity during this era. However, Montreal was just as significant a hotbed for comic book creation during this important phase of the Canadian Silver Age. The Quebec comics from the early 1970s were prolific and had a legacy that directly impacted French-language Canadian comic book creation for decades. Although rarely seen or discussed by English speaking audiences, the period is of such significance that comic historians generally refer to it as “le printemps de la bande dessinée québécoise” (translated to English as “The Springtime of Quebec Comics”).

In October, I presented a broad overview of the “dark period” of comic creation that preceded the Springtime of Quebec Comics (BDQ), which I dubbed, “La Grande Noirceur of Quebec Comics.” This dark period does not coincide with trends that were occurring elsewhere in Canada during the post-WECA era and is best thought of as its own distinct period of Canadian comic book research. If you have not already read my broad overview of the period, I recommend doing so: the Grande Noirceur had an important influence on the comic book output that I will be discussing today. Despite there being significant European and catechetical influences that impacted comic book creation in Quebec during “le printemps” that had little to no effect elsewhere in Canada, American superhero comics, humour magazines (such as Mad) and the fledgling Underground Comix scene directly influenced Quebec creators too. As such, the Springtime of BDQ does occur simultaneously with other movements within the Canadian Silver Age but is best thought of as a distinct collecting strain.

The Springtime of BDQ lasted approximately seven years, from 1968-1975. If you are comfortable with reading French, I recommend looking at Dr. Sylvain Lemay’s 2010 doctoral dissertation Le <<Printemps>> de la Bandes Dessinées Québécoise (1968-1975). Dr. Lemay’s treatment of the subject is, to date, the most in-depth history of the Springtime of BDQ. I also recommend Dr. Mira Falardeau’s 2008 book L’Histoire de la Bande Dessinée Québec for an excellent overview of the general history of Quebec comics. On the other hand, resources for English readers are sparse, but Collections Canada has a very thorough write-up about the history of Quebec comics available online that I suggest taking a look at if you are interested in this collecting strain. With all of this in mind, my goal this month is to flesh out some of this early material from the Springtime of BDQ in a way that has not been done before for English audiences, particularly insofar as certain creators and titles played a role in the creation of Croc in 1979, which is the longest-running title from the Canadian Silver Age other than Cerebus. That said, because of spatial constraints, this will be a broad overview that will (hopefully) lead to more in-depth examinations down the road.

As I mentioned in October, the Springtime of BDQ is generally thought to have begun with the coterie of creators who called themselves “Chiendent” (translated to English as “Grass”). In October, I erroneously stated that “Members included Jacques Hurtubise (aka Zyx), Réal Godbout, Gilles Thibault (aka Tibo) and Jacques Boivin.” I want to apologize to readers for this error, which I only noticed recently and resulted from last-minute edits I made immediately before submitting the article for review. In reality, Chiendent included poet Claude Haeffely and illustrators André Montpetit, Michel Fortier and Marc-Antoine Nadeau. Despite only producing strips for approximately six months (and producing several comic albums that were never published), Chiendent helped to free BDQ from its catechetical trappings and set the stage for the abovementioned creators (who I erroneously claimed were members of Chiendent) to embark on their own journeys as comic creators. It was never my intention to conflate the two.

I did mention the first two comic books released during this era in October, André Philibert’s Oror 70 (Celle qui en a marre tire) (roughly translated as “the one who is tired”) and Tibo’s L’Oeil Voyeur. Both of these comic albums were published by Éditions du Cri and the floodgates soon opened for an extensive amount of comic book creation in a short period of time.

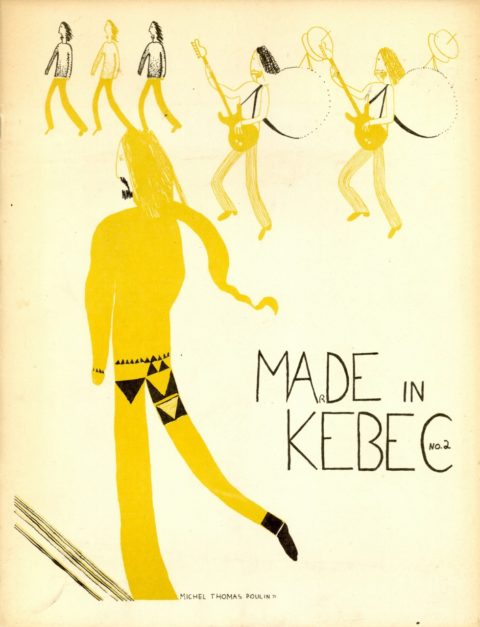

The first periodical BDQ comic series originated at the same time that the abovementioned comic albums were first offered for sale. Ma®de in Kébec (later Made in Kébec) was a five-issue series that was published in Sherbrooke beginning in June 1970. The first issue (usually called # 0) was unnumbered and was both shorter in length and smaller in dimension than the numbered series, which is magazine size and lasted for four issues from January 1971 to January 1972. The series was founded by André Boisvert (aka Bois’) and Fernand Choquette (aka Fern) and was published by Éditions Opus 3. The series featured contributions from several artists, including André Philibert and Nimus. From the outset, Ma®de in Kébec faced a series of obstacles that were part and parcel of BDQ during the early 1970s: geographical distance between creators making collaboration difficult, financial limitations, and irregular publication and distribution difficulties all led to the series ceasing publication by the beginning of 1972. Despite the series publishing 2,000 copies of the first two numbered issues and 4,000 copies of the final two issues, the series was not viable. Today, despite healthy print runs relative to other comics published during the Canadian Silver Age, issues of Ma®de in Kébec are almost impossible to find.

Other series that appeared early during this period did not manage to publish more than a single issue. For example, the rarely seen 1971 comics Pizza Puce by Emmanuel Nuno in Quebec City and Kébec Poudigne by Jacques Hurtubise (aka Zyx) and Jean Bernèche in Montreal did not make it to second issues. Both of these comics are so rare that I have never even seen copies of them (let alone pictures). Despite Kébec Poudigne only lasting for one issue, Hurtubise and some of his colleagues were able to take advantage of a sponsorship from the Service illustré d’animation culturelle de l’Université de Montréal that enabled them to publish two more comics from 1971 to 1972 called L’Hydrocéphale Illustré. This new series essentially launched the careers of Zyx, Françoise Barrett, Réal Godbout, Pierre Fournier and Gilles Desjardins.

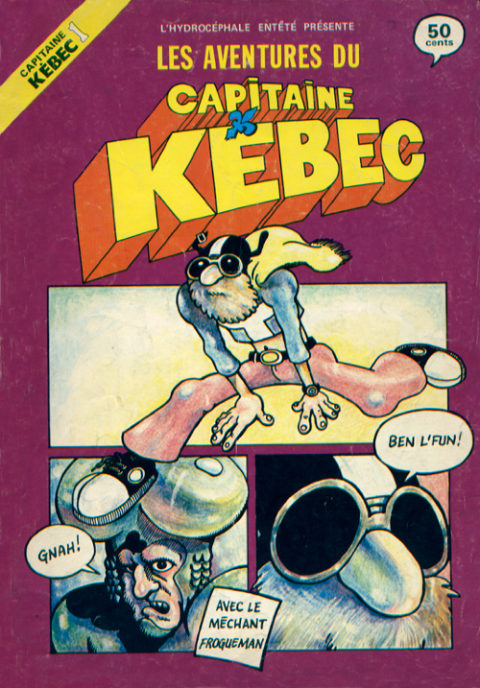

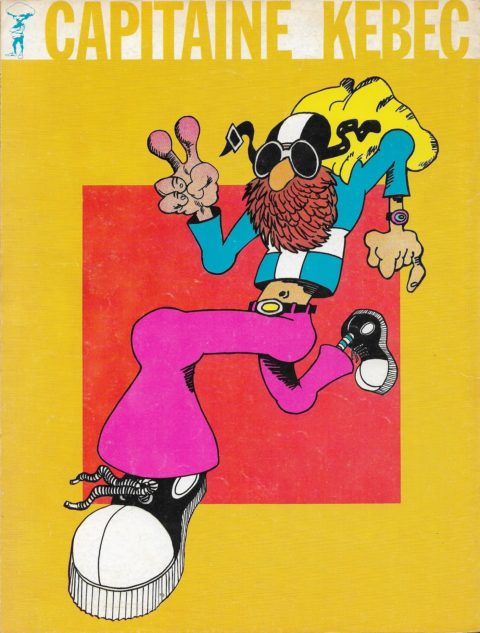

In 1972, Hurtubise left school to focus on comic books full time and decided against publishing additional issues of L’Hydrocéphale Illustré in order to improve his knowledge of the economics of comic publishing. Between publishing the two issues of L’Hydrocéphale Illustré, he earned an internship through the Office Franco-Québécois de la jeunesse that enabled him to meet numerous famous European creators, including Jean Giraud (aka Moebius). Shortly afterwards, he was able to procure another government grant and established a cooperative called the “Coopérative des Petits Dessins.” The group formed Éditions de l’Hydrocéphale Entêté and, in 1973, published what is arguably the most famous and most coveted of all of the comics released during the Springtime of BDQ: Les Aventures du Capitaine Kébec by Pierre Fournier. Then, in 1974, Petits Dessins signed a deal with the newspaper Le Jour to provide daily comic strips, the most famous of which is arguably Zyx’s own Le Sombre Vilain. The newspaper continued to publish daily comics produced by Petits Dessins until 1976, when it switched to a weekly publication before ceasing operations entirely in 1978.

Capitaine Kébec is unusual insofar as the character only starred in the single eponymous comic (and making an appearance in the group’s next comic) before essentially disappearing for nearly a decade. Nevertheless, the character became a key symbol of BDQ during the 1970s. As stated in Robert MacMillan’s Encyclopedia of Canadian Animation, Cartooning, Illustration, “‘Capitaine Kébec’ like ‘Captain Canada’ is a story which takes the motif of the costumed hero as the embodiment of established values and attitudes, turns that motif upside down and uses it to question and criticize those same established values and attitudes…In ‘Capitaine Kébec’ the hero embodies the alternative values and attitudes and is attacked by an establishment villain.” As such, Fournier’s character comes across as an anti-establishment hero that is breaking away from the religious conservatism of La Grande Noirceur. The comic had a sizeable print run of 18,000 copies, which helped contribute to its success as a symbol of 1970s BDQ. Today, the comic rarely comes up for sale and high-grade copies can sell for hundreds of dollars.

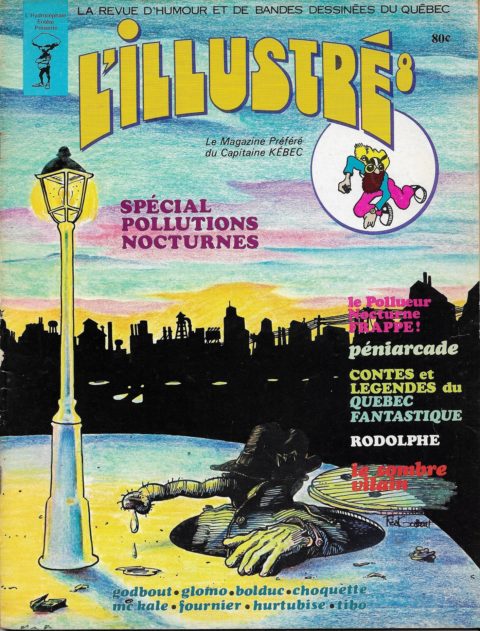

1974 also saw Hurtubise bringing his own group of established co-creators together with Fernand Chocquette and numerous contributors to Ma®de in Kébec to publish the one-shot L’Illustré. Despite being a one-shot, the issue was released as # 8, referencing the eight major artists who contributed to the issue who are named on the front cover. The comic features a who’s who of Quebec comic creators from the Springtime of BDQ, including Réal Godbout, Alain Glomo, Fernand Choquette, Pierre Fournier, Daniel McKale, François LeBlanc, Jean Bernèche, Zyx, Tibo and Vo Van Huy. Other contributors included Dan May, Gilles Desjardins, Jean Guy Pelletier and future comic historian Mira Falardeau.

Unfortunately, a second issue of Les Aventures du Capitaine Kébec never materialized, despite being advertised in L’Illustré. Indeed, the company did not release another comic book ever again and apparently ceased publication altogether, though the activities of Petits Dessins continued and the contributors to L’Illustré created comics for various other newspapers and comic companies throughout the 1970s. Even so, L’Illustré set the stage and tone of what would become Croc five years later and is now considered an important forbearer of Croc.

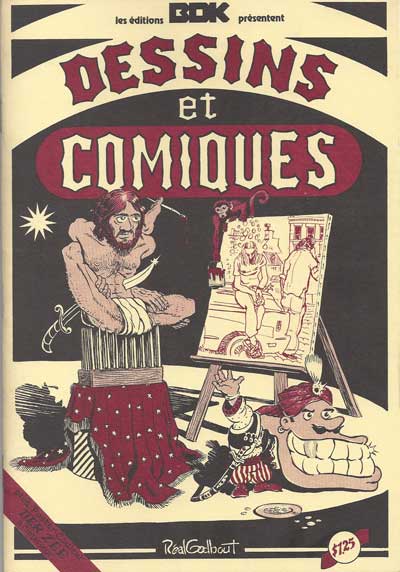

Godbout, Desjardins and Bernèche all continued to work regularly in comics during the latter half of the 1970s. Godbout’s most famous character of the decade, Michel Risque (a parody of James Bond and Bob Morane) first appeared in André Carpentier’s 1975 book La bande dessinée kébécoise and subsequently made appearances in the counterculture journal Mainmise. He then published his first comic book album, Dessins et Comiques, through the newly established company Éditions BDK in 1977. Desjardins also released his own album through Éditions BDK in 1977 called Crimpof. Bernèche followed suit with his own album in 1978 called Rodolphe, featuring the character that had appeared in L’Illustré. Other creators, such as Zyx and Fournier continued to hone their craft with their newspaper strips and contributions to the new series Prisme from 1976 to 1977. Unfortunately, these albums and series did not sell particularly well. For example, Dessins et Comiques only had a print run of 500 copies.

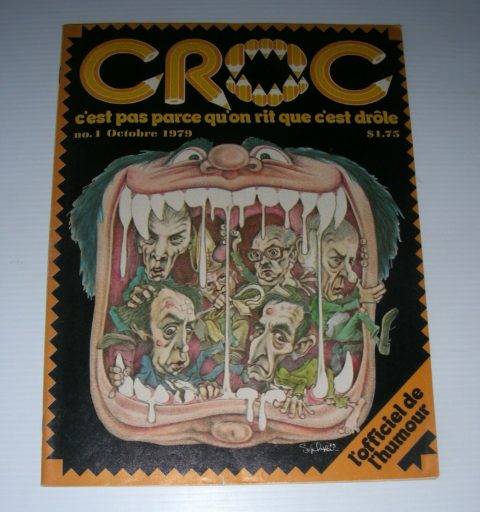

By 1979, Hurtubise was ready for another attempt at a collaborative comic series and procured an $80,000 grant from the ministère des Affaires culturelles du Québec. However, by this point (according to Collections Canada), Hurtubise had concluded that the Quebec market was too small to accommodate a monthly comic series and changed direction to publish a humour magazine supplemented by comic strips. The new publication team also included Hélène Fleury, Roch Côté and Pierre Huet. The result was Croc, which debuted in October 1979. The closest comparable to the series are American humour magazines like Mad, Cracked and Crazy. The series would become a mainstay of the Quebec BD scene and would help to launch the careers of aspiring creators, while also bringing back some of Hurtubise’s previous collaborators into the fold (particularly Godbout and Fournier). The series would last for 189 issues, ending in 1995.

Croc started as a lean operation, but unlike Hurtubise’s earlier endeavours immediately started with sizeable distribution within the Quebec market, with early issues having print runs of approximately 20,000 copies. The series quickly gained an audience and by its eighth issue had a circulation of 50,000 copies. By 1984, Croc had a regular circulation of 75,000 issues every month and employed over 100 people (including part-timers and freelancers). At its height, Croc became a multimedia powerhouse that included merchandise, board games, comic albums, a radio series from 1986-1987 (Radio-Croc) and a 1988 television series (Le Monde Selon Croc). Hurtubise even published his own official version of Mad in the early 1990s called Mad-Québec.

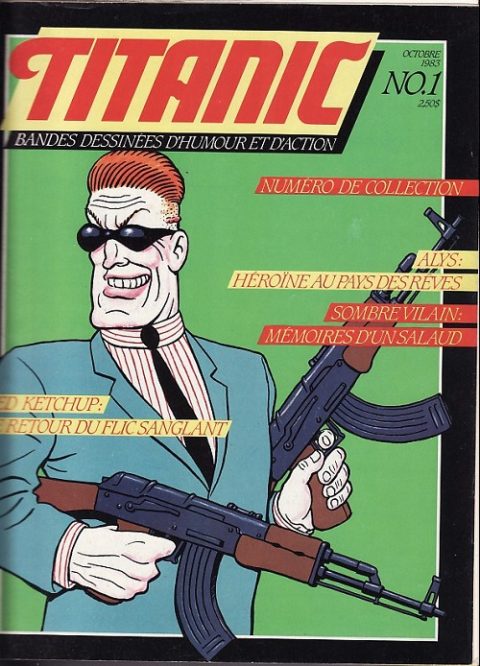

The success of Croc allowed Hurtubise to make one more attempt at publishing a monthly comic series, Titanic, which launched in 1983. Despite the series featuring the return of Capitaine Kébec and featuring a new character from Godbout and Fournier called “Red Ketchup” (which would go on to become one of the most famous comic characters from 1980s Quebec), the series did not sell well and ended after 12 issues.

Croc and Titanic also inspired a number of copycats, including the short-lived series’ Cocktail, Tchiize and Iceberg. However, the success of the humour magazine itself led to the emergence of its long-running rival, Safirir, which debuted in 1987 and lasted until 2016, ending with issue # 288. Despite Safirir lasting much longer than Croc, Hurtubise’s series remains an important part of the Canadian Silver Age; whereas, the bulk of Safirir was published in the era afterwards.

After Croc published its final issue in 1995, Hurtubise switched to focusing more and more on computer software. He was inducted into the Canadian Comic Book Hall of Fame in 2007 and passed away from a devastating heart attack on December 11, 2015. This week is the anniversary of his death, which is one of the reasons why I decided to highlight the work of Zyx this month. In reality, the history of BDQ during the Canadian Silver Age is dense and my overview here barely scratches the surface of this significant collecting strain. Nevertheless, the impact of Jacques Hurtubise on the medium as a publisher, editor, artist and overall champion of the medium should not and cannot be understated. Every time that I delve into BDQ from the 1970s and 1980s my inquiries always lead back to Hurtubise, even if only in a peripheral way. Quebec comics and Canadian comics more generally were made better as a result of his endeavours.

It’s hard to believe that Forgotten Silver has been published every month at Comic Book Daily for a year now and that this is the thirteenth entry into my series about the history of the Canadian Silver Age. I have a lot of plans for entries in 2020, but I want to know what you, the audience, would like to see more of. Please let me know in the comments section.

With December upon us and numerous holidays around the corner, I want to wish everyone a Merry Christmas, Happy Hanukkah and the very best for any other holiday that you may be celebrating this time of year. I know that I will be setting aside some “me time” to dust off some old comics to read during my holiday break and I hope you are able to do the same!

I’ve always considered my knowledge of comics from Quebec to be lacking. Thank you for your study of these materials. Enjoy your time off and the season.

This Sylvain Lemay of which you speak wouldn’t be one of the boys from Cosmix comic shop would it? Hello from the Toronto area Sylvain.

Wow, he’s been around a long time. He knows his stuff and is a friendly guy to boot. Nice article brian, and I echo Tony’s sentiments, Merry Christmas to you and yours and happy Holidays!

Thanks, Tony. I am glad you enjoyed the article. BDQ is a large collecting strain within the Canadian Silver Age and is both fascinating and fun to collect. I am happy to be able to present this material for an English language audience because it is so interesting. Hope you have a great holiday too!

Jim, I don’t know the answer to your question, but I suspect that the Sylvain Lemay you are talking about is a different person, as Dr. Lemay teaches at Université du Québec en Outaouais. He reads Forgotten Silver sometimes, so maybe he will chime in to clear this up. Hope you have a great Christmas too!

Here is a link to an article with biographical information about Dr. Lemay that appeared in “Le Droit” the other day, which might help: https://www.ledroit.com/actualites/personnalite-de-la-semaine/sylvain-lemay-pionnier-de-la-bd-a-luqo-b5f5d277e3d8cce4cd07f9863cebbb92

Hey Brian

Number one on my wish list for future posts is a look at the mini comic explosion of the ’80s with particular reference to the works of Chester Brown (Yummy Fur), Julie Doucet (Dirty Plotte), John MacLeod (Dishman) and the incredibly eclectic output of Colin Upton. These four make up a significant collecting strain of the Forgotten Silver Age and all four of them made the jump into conventional comics later in their careers. Chester remains one of Canada’s most compelling creators to this day. I have been trying also to find the significant point of connection between these books and the punk rock minis that seem to have preceded them. Photocopy technology at the time certainly made anyone capable of producing a significant body of work and the profusion of titles I remember on the shelves at the Beguiilng made for some of the most interesting and diverse product of the period.

I’ve really enjoyed your focus on the Quebecois creators. This is an area which is rarely covered in any consideration of Canadian comics and bears a lot more coverage in future columns, maybe focusing on the major individual creators. Anyroad, whatever you put out is bound to keep us entertained for the next year of Forgotten Silver Age and beyond, and congratulations on hitting Lucky 13 of the series!

so long for now, mel

Thanks for your input, mel. I agree that it would be good to dedicate a column to some minis, especially considering the breadth of material from the era. I am going to keep this in mind and might try to do something along these lines early in the new year.